It’s easy to build a society that can meet our needs if we can start with ideal conditions. If there are

no limits, no restrictions, no vested interests, no constitutions, no laws that

previous generations have declared are immutable and have set up police,

militaries, and prisons to enforce, people merely have to decide what they

want, vote on it, and if approved, make the necessary changes.

Natural law societies give us these ‘no-limit’ societies that we can

easily alter into any other societies. Natural law societies are essentially

‘blank-slate societies.’ They are built on the belief that we, the members of

the human race, are servants of nature, not its masters, and we must conform to

its rules or we will perish. They are built on the belief that the very idea of believing humans can own planets

or parts of planets is totally nonsense, and only people who are deluded are

likely to be able to believe it. Ownability is just as impossible for groups of

people as individuals, even if the groups of

people call themselves ‘nations.’

Since they don’t believe in ownability, they don’t believe that

‘nations’ can even exist. If there are no nations, there are no borders, no

border disputes, no national debts, no inflexible and antagonistic

‘constitutions’ or other immutable laws that might lead to conflict; there are

no ownable corporations with legal rights (such rights require people to accept

that they or their governments have the authority to grant them), no

obligations to contracts or nations, no special rights for minorities of the

population to get special advantages from the land. If we start with natural

law societies, we start with blank slates, with no obstacles based on special

rights to the good things the world produces that people would fight or resist.

The ‘journey through possible societies’ explained in the last few chapters started with this ‘blank-slate society’

and then moved from there to systems that had greater

ownability to permanently productive properties, like parts of planets and

long-term cooperative structures.

It is easy to move in this

direction.

People are always happy to accept situations that make more rights available to people who want

to pay for them. They won’t resist or fight against these kinds of changes.

Realistic

Change

Unfortunately, you and I were not born into ‘blank-slate societies.’ We

were born into societies that already had nations, debts, owners, vested

corporations, and a great many other realities that grant specific rights to

small groups of people at the expense of humankind as a whole. All this existed

long before anyone now alive was even born. The societies we were born into are

extreme societies, which grant the maximum possible rights to individuals and

minorities (like the citizens of ‘nations’) of the of the human race.

This means that if we start with these extreme societies, and move upward through the range of possible

societies (toward sustainable

societies, and then eventually—if we keep going—to socratic leasehold ownership

societies, and finally back to natural law societies), our journey will have

different dynamics than one that moves downward. The movement upward will

require more planning than a movement downward, because it will have to be

organized so that the groups that find their special rights to the world declining must have other rights (general

rights that go to the human race as a whole, for example) increasing, so that they gain more than

they lose, or they will lose rights and wealth during the transition phase.

People don’t want to lose rights and wealth.

They have incentives to resist

changes that cause them to lose rights and wealth.

If we want a smooth transition, without trauma, we will have to use our

intellect to work out the flows of value during the transition phase, to make

sure that all groups benefit. This not anything like fighting or having a

‘revolution.’ Violence is a primal reaction to adversity: it is a last resort

that nature programs into the beings of all animals to allow them to survive

after all non-violent options have been exhausted. We have seen revolutions and

violence over and over again. This approach has been proven not to work.

Einstein defined ‘insanity’ as ‘trying things you know don’t work, over and

over, in the hope of getting different results.’

A

Scientific Approach

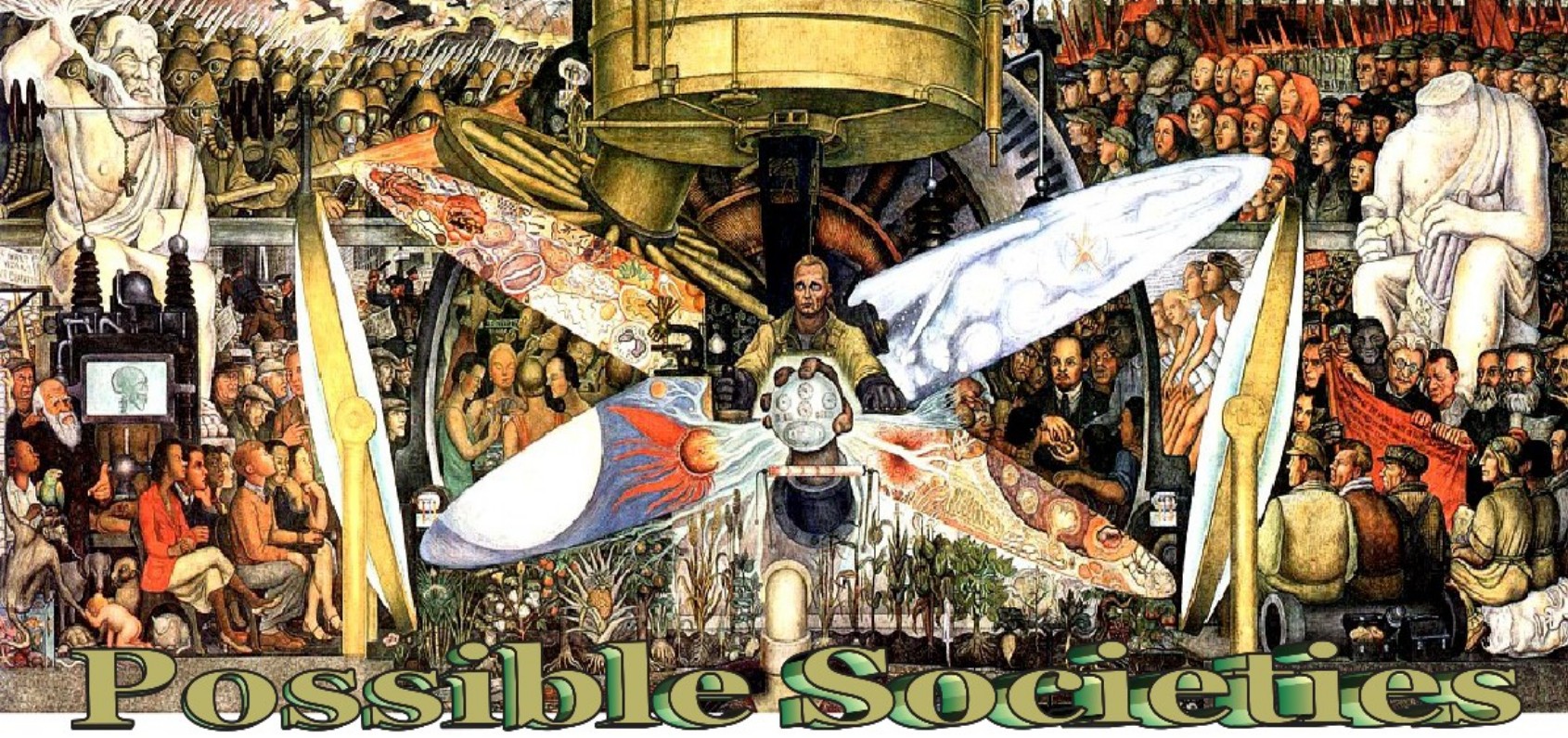

Possible Societies (Books One and Two combined) was designed to make it

clear that the ‘modes of existence’ that humans have had in the past are not

the only possible modes of

existence. Natural law societies and sovereign law societies are both extreme societies, one built on the belief

that 0% of the rights to the world are ownable, the other built on the belief

that 100% of the rights to the world are ownable. Possible Societies was

designed to show that we don’t have to base our societies on guesses (beliefs;

mental convictions which, by definition, can’t

be proven with science) about whether some power that is above us all wants us

to take care of the planet or fight over it (say nature, which may want us to

take care of the planet, or God, which may want us to ‘dominate and subdue’ the

world).

We have the ability to

use our intellect, to figure out other ways to interact with the world. If we

want, we can use our intellects to work out options that are not absolute

non-ownability societies, and not absolute (sovereign) ownability societies,

but where the human race considers itself to be the landlords of the world,

with the ability to grant its members specific rights to the world, without having

to accept absolute ownability of all rights to the world. Book One of Possible

Societies was designed to provide arguments to the effect that other societies

are possible. Although Book One

did discuss all of the options, it did so only superficially, because to prove

something is possible, it is only necessary to come up with one example. Book

One focused on the idea of building societies around an intermediate kind of

property control called ‘socratic leasehold ownership,’ explaining this

intermediate option in detail, in an attempt to convince as many people as

possible that the human race really is capable

of having intellect-based societies.

A society is not really possible

if it can’t be formed unless certain conditions are met, and these conditions

can’t possibly be met. In order to show that intellect-based societies are

truly possible, I had to show that the human race has enough tools at its

disposal to meet the conditions needed to convert to socratic leasehold

ownership societies, if we decide we want to accept the underlying premises of

intellect-based societies (specifically, that we are the dominant species on

Earth, making us the lords of the land).

Book One was designed for ‘lay audiences,’ which means people without

any extensive scientific or mathematical background in fields related to the

issue being discussed.

It had a specific purpose: I am trying to create a state of mind. I hope to be able to create this state of

mind in enough people to create a kind of movement, where people who think this

way work together to make changes that, if made, will gradually move the planet

away from the societies you and I were born into and raised in.

This state of mind accepts

science and its findings and is willing to use logic and reason to understand

and deal with issues that people have traditionally used beliefs, emotions,

feelings, and guesses about the intentions of invisible beings who are presumed

to have control over earthly events with desires they keep hidden from us. It

basically means ‘accepting reality,’ at least for the sake of argument and

discussion. If we accept reality exists and is real (again, even for just the

sake of argument and discussion), and don’t try to temper or mix our logical

analysis with modes of thought that derive from the less

intellectually-inclined parts of our minds, we can easily see the evidence that

the human race is almost certainly the dominant species of being on this

planet, and therefore in charge of its own destiny.

The contrast: the human race may be nothing but minions of invisible

superbeings with hidden agendas. If this is true—and it might be—then nothing

we do will make any difference and there is no point in doing anything but

prepare for death. However, if we accept—again, just for the sake of

argument—that reality might be real, and humans might be the dominant species, and work

out a plan of action based on ‘what options we would have if reality turns out to be real,’ we can

then decide if we prefer to accept reality as real or accept the beliefs handed

down to us by past generations.

Scientific evidence tells us that the human race evolved over a period of billions of

years, as a result of scientifically explainable processes. In other words, the

science contradicts the view that

some superhuman being created us and therefore has designs and intentions for

us, that we can only guess about.

Scientific evidence tells us that the current conditions of our ‘modes

of existence’ or ‘societies’ are the understandable and predictable results of

actions taken by people who lived before us, of things they raised their

children to accept and believe, and of the beliefs that have been passed down

to our current generation. There is no scientific evidence supporting the

widespread belief that the events and conditions of our societies are due to

the intentions of invisible superbeings. We can understand everything we see

around us without having to

resort to supernatural explanations.

Scientific evidence tells

us that humans are capable of

modes of existence that are entirely different than those that dominate the

world today. History, in the form of eyewitness accounts from the last few

centuries, written records, and as derived from anthropological studies of

archeological sites, tells us that humans organized their existence in

different ways in the past. This provides proof that other human modes of

existence or societies are possible. We are capable of more. To reject this, we

must reject science, history, and unlimited evidence of our own eyes.

All of the discussions of Book One were designed to help people attain

this kind of mental attitude. I am not trying to get you to reject the beliefs of the past, only to be

able to accept that it is possible

that they may not be correct. It is possible

that reality is real, science gives us correct answers, and the things we see

happening with our own eyes are really happening. If you can accept that this

is possible, you can easily see that, if indeed reality is real, the human race

is not doomed. We have real hope.

Logic and reason can provide answers that beliefs and guesses about the desires

of unseen beings can’t provide.

If enough people can

attain this enlightened state of mind, we can work together (without needing

vindication or acceptance by the people who don’t have this state of mind) to

start initiating changes that will alter the mechanical structures of our

societies. In order to create this state of mind in people without a scientific understanding of the

different ways human societies can work, I had to cut a few corners and leave

out a few complicated arguments. As a result, I would expect that people with

very inquiring minds may have had questions about issues that couldn’t be

explained without a great deal of math, and therefore weren’t explained in Book

One. Some people may have felt that the changes described in Book One were too

good to be true, and nothing therefore but wishful thinking.

The absolute proof that

the human race can move from the societies we were born into to societies that

can meet our needs is technical, and mathematical. If you don’t have the

necessary background, some of the discussions of Book One may have been pretty

hard to accept. They can be

proven, but the proof requires understanding of very complex topics that I

didn’t want to introduce in Book One for fear of losing the great bulk of

potential readers.

Let me give you an example to show what I mean:

The relationship between high risk-free rates of return on money and

destruction is quite complex, but it is well understand and accepted among

people who understand it. Since I have discussed it several times in the book,

I will not go over it again in the text, but have put a brief explanation in

the text box to refresh your memory.

If the rate of growth in money (the rate at which people get rich) is higher than the natural rate of growth of

resources, people can get rich by destroying resources, so they have incentives

to destroy resources and sell the resources for money, to convert their wealth

into the form that grows faster.

For example: A healthy forest grows at 2%. This is the maximum income

you can get through sustainable forestry.

If you can get 20% without risk or effort (this was the risk-free rate in the

early 1980s), you will get 10 times more

income from your wealth by converting the lumber into money than by managing

the forest for the maximum sustainable yield. If you leave even a single tree

you are missing out on returns you could get if you killed this tree, so you

are losing money if you leave a

single tree alive. If you wait even a day longer than necessary to destroy the

forest, you miss a day of the higher returns, so you are losing money to wait. You not only have

incentives to destroy the forest, but to destroy it as thoroughly and rapidly as you can manage.

This relationship is well understood and not introduced in this book by

any stretch of the imagination. A lot of people understand it.

Chapter 11 showed that, if we move to socratic leasehold ownership

societies, we will divert a great deal of the money that now flows to money as

risk-free returns. As this happens, the risk-free rate of return will have to

fall. (The rate of return is the

return per dollar of invested money. If people who get free money as returns

get less in free money, because some of the free money goes to the human race,

but they have the same amount of dollars invested, they have to get lower rates of return.) As the risk-free rate of

return on money falls, the rewards

for destruction fall, and the strength of

destructive incentives falls.

If the risk-free rate of return on money falls to the same rate as

natural growth of resources (2% or so in the case of forests), then destruction

is no longer profitable, it is only a ‘break even’ transaction. If the

risk-free rate of return on money falls below

the rate of natural growth of resources, destruction is a money-losing proposition. People are

better off financially (they make more money) interacting with forests as if

they treat the land as sustainable tree farms, rather than as if they are cash

registers that they can raid to get money to use to collect the much higher

rates of return offered on money assets.

If you don’t understand the scientific reason that rates of return must

fall, the claim that destructive incentives would not exist in socratic

leasehold ownership societies might have seemed to be nothing but a hoped-for

result that couldn’t be justified logically. If you understand the science,

however, you can see that it absolutely has to be true. As you saw in the

‘journey through possible societies,’ there it would be possible to build a

leasehold ownership system where the prices

of private property rights are so low that they would be trivial. In ‘virtual

rental leasehold ownership societies,’ for example, the ‘price’ of the property

rights to the Pastland Farm would be a mere 24¢.

The price of the

leasehold is the amount invested

in it. In a virtual rental leasehold ownership system, only a few pennies will

be needed to make all of the investments in the world. The demand for investment money will be almost

zero. The supply of investment

money (the amount of savings in the society that people would like to invest)

will be far, far, higher. If the demand for anything is very low and the supply

is very high, the price must fall. It will fall until the supply and demand are

in balance. Since it would never be possible for the demand for investment

money to equal the supply (no matter how low interest or return rates go), the

‘price’ of money, or the interest/return rate, would have to fall as far as it

could go, to zero, and stay there.

If you understand the science, you know this has to be true in ‘virtual rental leasehold ownership

societies.’

In fact, the price of money (the risk-free rate of interest or returns)

has to be zero in all societies

where the demand for money is lower than the supply.

As you saw in the last few chapters, if we start with a virtual rental

leasehold ownership system, and move downward in the range (to societies with

higher price leasehold payment ratios), the prices

go up. The price is the amount

invested, so the amount of money invested, and the demand for investment money must also go up. There will be a

point, in this range, when the demand will rise to the level of the supply of

investable money. Although we can’t tell exactly

where this point will come without knowing a great many details of the specific

society, we know that there is a limit of investable money (provided we use

treasure-based money, rather than fiat money), because there is a limit to the

amount of real value or ‘treasure’ that can be in storage, backing money. In

this example, I picked a number for the investable money supply of $10 million.

When the demand for investment money gets up to $10 million, the demand

and supply will be in balance. This is the lowest

option on the road map of possible societies that can possibly have a zero

risk-free interest/return rate on money. As a result, this is the lowest option in the road map of possible

societies that can possibly have zero strength destructive incentives.

All options below

socratic leasehold ownership have demand for investment money that is higher

than the supply. If the demand for something exceeds the supply, the price of that thing must go up. The price of money is the interest or return

rate that people must pay to people who have money to get to use it. After

socratic leasehold ownership, the rate of return on money must go up above what it was before.

Since the rate before was always equal to the rate investors needed to

justify risk (investors won’t invest unless they get enough to compensate them

for risk), if the rate goes up above this, any increase must be a risk-free

rate.

If we understand this, we can understand exactly why it would be possible make the claim

that socratic leasehold ownership societies have zero percent risk-free

return/interest rates, so this particular enormous source of rewards for

destroyers won’t exist. The societies we live in now, and all societies below socratic leasehold ownership on the

road map of possible societies, pay people to destroy our world. Socratic

leasehold ownership societies are the first societies we get to where this does

not happen.

I want to repeat that this (long) example involving interest rates is

just an example. I am trying to show you that many of the claims that may have

appeared to be overzealous about the way society would change when you read

Chapter 11 can be shown to be scientific and mathematical certainties, using

the scientific background explained in the last few chapters.

Trip

Planning

On a regular road map of a part of the world, we can plan journeys. We

can identify our starting position, on the map, the end point we would wish to

reach, and then work through the various different roads that can get us there.

The same is true for transitions between societies. We know where we are on the

road map of possible societies. We can identify an intended destination or, at

the very least, a direction that

we would like to travel.

As we saw in Books One and Two of this series, there are paths from

sovereign law societies to other societies. (Book One showed that Alexander the

Great, working with the great scientist Aristotle and advancing on the

principles of societal construction that Socrates and Plato worked out, was

able to put a society built on the same principles this book explains in place,

albeit for only a very short period of time. Book One explained a different

option, taking advantage of modern tools like the internet and global

humanitarian corporations, to create a gradual transition to one specific type

of society, a global socratic leasehold ownership society.)

These are paths from one place (one type of society) on the road map of

possible societies to a different place (different type of society). If you

look at any road map of any part of the planet, you will be able to see that

there are actually infinite ways to get from any point on the map to any other.

(For example, to get to St Paul to Minneapolis, you can take I94. You could

also take Franklin Ave. You could swim the Mississippi river at any of millions

of different locations. You could also head east to New York, take a train to

Cape Canaveral, get on a rocket, stop at the moon and plant a flag, come back

and splash down in the Pacific Ocean, take a jet ski to San Francisco, and then

take a jet to the Minneapolis airport. There are infinite options.)

The same is true for making transitions between societies. There are as

many ways to get there as there are thoughts that humans can think.

Some options are quite difficult and no sane person would be likely to

actually consider them as practical.

(For example, I have never heard of anyone trying to get from St Paul to

Minneapolis by the route described above, which goes by way of the moon. It may

be possible. But it is so far

from practicality that no sane person would suggest trying it.)

Perhaps there is no easy

way to get from where you are to where you want to go. In the movie two women

had to get from Arkansas to Mexico to avoid being arrested for killing a man,

but they couldn’t go through Texas. There is no easy way to get to Mexico from Arkansas without going

through Texas. (After looking at the map, Thelma told Louise that there is

nothing between Arkansas and Mexico except

Texas.) But that doesn’t mean that no one can get to Mexico from Arkansas

without going through Texas. If you have enough of a motivation to get there,

you can make it.

It is not as easy to get

to societies that can meet the long-term needs of the human race from sovereign

law societies as from natural law societies. But it can be done.

Chapter 11 of Book One (Possible Societies), explained a possible way

to get from sovereign law societies to socratic leasehold ownership societies.

The discussions in Chapter 11 were designed for people who only had the most

superficial introduction to the science behind the operation of societies built

on different ways of interacting with the world we live on. At this point, I

want to explain the same example again, filling in a few of the discussions

that wouldn’t have been understandable without the scientific background

presented in Book Three.

Cosmos

Revisted

Once again, I want to try to depersonalize the discussions involving

change. I want to do this for the same reason Socrates did it, when he created

the idea of a hypothetical continent of ‘Atlantis’ to discuss the problems of

society and the steps required to repair them. He did this because he knew that

people got very emotional about

discussions involving change, because they took them personally. They had been

raised to believe that ‘nations’ are real things and can be either ‘good’ or

‘evil;’ they had been raised to believe that a certain nation was ‘their own

nation’ and that they had a natural responsibility to preserve ‘their own

nation’ in its same basic form, and resist any attempts to alter ‘their own’

nations, by any means necessary. (They had to kill Socrates to get him to stop

‘corrupting youth’ by telling youth things that might lead to change, so they

killed him. They had been raised to believe that nothing is more important than preserving the integrity of

‘their nation.’)

Emotion doesn’t help us

understand the idea of a transition between societies. It harms understanding. Emotion is, in many

ways, the antithesis of logic: when we revert to emotion, we have mental

excuses to abandon things that we know make sense and must be done. (‘It just

doesn’t feel right,’ I am often

told. Of course not: We were raised by people who worked very hard to make us feel that nations are real things, even

though logic and reason tell us they are made up. It never feels right to use logic in areas where we

have been trained to think illogically.) I will to depersonalize the ‘reverse

journey’ by setting it on another world. This other world does not have a

‘United States,’ it doesn’t have a ‘China,’ and none of the other ‘nations’ on

this other world match the names and specific details of any nations on Earth.

You don’t have to worry about changes on this other world affecting anything

you believe in or care about, because this other world is so remote from Earth

that nothing that happens there could ever affect you or anyone you care about.

Scientists

have determined that there are somewhere between 10 billion and 20 billion

‘Earth-like’ planets in our galaxy, which would imply that there would have to

be between 4 quintillion and 8 quintillion Earth-like planets in the parts of

space visible from Earth. If the events that lead to the evolution of sapient

beings are possible here (and they are, because we are here), they must be

possible elsewhere. Perhaps they are quite rare. But it would be arrogant in

the extreme to claim that they are so rare that, out of quintillions of planets

where such an evolution could have taken place, we have the only one where it

did take place.

I will call this other planet ‘Cosmos.’

Cosmos is roughly the size and weight as Earth, with roughly the same

percentage ocean coverage as Earth, and roughly the same climate as Earth.

Early life appeared on Cosmos some 3.6 billion years ago. Natural selection

worked on Cosmos as on Earth to ‘select’ more capable beings and, over billions

of years, complex animals evolved. Eventually beings that called themselves

‘humans’ evolved. These beings were self-aware, thinking beings.

The first humans were not fully confident in their intellectual

abilities. They tended to rely on superstition, beliefs, feelings, and

emotions. They surmised that the things Cosmos provided for them were gifts from

nature, which they thought of as a higher power and force than humans. They

formed natural law societies. Natural law societies don’t naturally reward

innovation, invention, progress, or advancement in technology. They don’t have

constructive incentives. All living things must react to incentives (they must

figure out and practice behaviors that help them meet their needs). The

inherent incentives of the early societies on Cosmos pushed for stagnancy and

these societies were stagnant for millions of years.

As

Volume One showed, the transition between natural law societies and sovereign

law societies on Earth took 5,894 years to complete.

The

transition started roughly 4004BC by our current calendar (this corresponds

with the first verifiable history of wars between nations; it is also

considered to be the beginning of time by believers in the ‘Old Testament,’

which includes all ‘western’ religions). The final official campaign in the

transition, marking the end of organized resistance to societal change, took

place on December 29, 1890, when the last significant group of people who

refused to accept the authority of the ‘nation’ that had conquered them were

machine gunned and dumped into trenches at a site called ‘Wounded Knee,’ now a

part of the state of South Dakota. ( to pictures.)

One day, a group somewhere decided that the world was ownable. That

group created the type of society this book calls a ‘sovereign law society.’

The owners owned everything. This society has inherent incentives that lead to progress

and growth. The people in this society wanted more land and had the ability to

take it. Over the course of 6,000 years, they kept taking more and more land,

eventually taking over the entire planet.

When we first visit Cosmos, it is divided into roughly 200 ‘nations’ of

various sizes, spread over the 60 million square miles of land surface of the

planet. Its population is roughly 8 billion people. Several nations have

massive arsenals and many nations devote such massive amounts of wealth to weapons

and have economies that many call ‘military industrial complexes.’ To make

weapons more efficiently, these nations have created formal organizations

called ‘corporations’ and given these corporations roughly the same powers and

authorities that Earth corporations have.

Censorship

of the internet:

Governments

try of course, and can succeed as long as people don’t decide to take advantage

of simple tools to alter the communication protocols and communicate through

gateways set up with alternate architectures. Most people with any computer

savvy at all today know that there are various ‘dark webs’ which are structured

so that governments can’t prevent them from operating. (On the ‘dark web’

anyone can buy items that are illegal everywhere, including weapons of mass

destruction.) The existence of sites that governments would very much like to

shut down, and of the ‘dark web,’ tells us that the web can’t be censored.

Only a few decades before we visit Cosmos, its weapons-makers made the

planet’s first nuclear bombs. Nuclear weapons generate massive electromagnetic

pulses that destroy simple communication systems. The military planners

realized they needed an open-architecture communication system. They needed the

architecture to be open (non-standardized) to make it impossible for enemies to

shut down or censor their new ‘internet.’ The open architecture also meant,

however, that even the nations that created the internet couldn’t censor it in

any effective way.

Now the people of Cosmos have access to several important tools that

they can use to alter the nature of their society, including giant,

multi-national, humanitarian corporations and internet websites.

Change

On Cosmos

Change started when a man named ‘Henri Dunant’ formed a global

humanitarian corporation.

Dunant had some business dealings with people with cash-flow generating

properties. These people wanted to set up a system so that the income from these properties would benefit

the human race going forward. They didn’t want any government involved.

This

discussion roughly parallels the work of the Earth Henri Dunant, as explained

in detail on Book One, . The Earth Dunant did his best to form an organization

like the one described below, but his work was thwarted by powerful people who

believed it was morally incorrect (inconsistent with the ideas in the Bible) to

interfere in events in the world in ways that would alter the basic structures,

including ‘nations.’ As you saw in Book One, the Earth critics fought Dunant in

court, eventually forcing him into bankruptcy, unable to pay his legal fees.

Although the organization that Dunant created (the International Red Cross) has

done some wonderful things, it never took the form that Dunant intended for it.

They wanted decisions about this money to be made entirely by an

organization that was not affiliated with any nation or government on Cosmos.

The philanthropists who wanted Dunant to set up this organization were trying

to find a way to advance the interests of the human race as a whole, not some group of people who happened to

have been born inside a certain configuration of imaginary lines. They wanted

an organization that would bring the human race together into a true

‘community,’ and give this ‘community of humans’ a forum and revenue it could use

to advance the interests of the human race as a whole.

Dunant decided to call the new humanitarian organization he would form

‘the Community of Humankind.’

Dunant didn’t want to guess about the best way to organize the

Community of Humankind so it could do the most good. He traveled around the

world to find the best property management people on the planet. He organized a

conference for them to discuss the issue and present options to him and his

backers, so they could make an informed decision about the best way to

accomplish their goals.

One of the recommendations stood out. It recommended that the

humanitarian organization to create leaseholds for the cash-flow generating

proprieties, sell the leaseholds, and then use the income from the leasehold

payments to provide humanitarian services.

Dunant set up this system.

He originally set it up for the philanthropists who had asked him to

set up the organization. But these people were happy to have an organization

that had an even wider scope, and fully approved when Dunant suggested making

this system available to everyone who wanted to take advantage of it.

Dunant set up a web site that would allow anyone to participate. If any

inhabitant of Cosmos owned any kind of property that generated free cash flows

(including either corporate stock or real estate), and wanted the entire human

race to benefit from the existence of these flows of free value, she could

download and fill out a simple form from the internet.

During the lifetime of the benefactor, nothing would change. After she

died, the property would transfer to the control of the Community of Humankind.

The Community of Humankind would then create a leasehold on the property and

sell it. The landlords of the

property in question would now be the members of the human race, as represented

by the Community of Humankind. Income from the property would flow from the

land to the landlords automatically and without risk, and the leasehold owners

would be able to use their land for anything that freehold owners could use

their land for, except certain

uses on a list; they would have to get landlord permission first if they wanted

to use their land for any of the uses on this list.

Exponential

Growth

The system Dunant set up on Cosmos is a ‘one

way’ system.

Freeholds become leaseholds.

But leaseholds can never become freeholds.

Each additional property that ‘gets into the

system’ (converts from a freehold to a leasehold) means higher incomes for the landlords, the members of the human race.

When Dunant was setting up the system, he

was told that there are infinite numbers of ways to set up leasehold ownership

systems. His experts analyzed them, as discussed in the last few chapters, and

explained the incentives inherent in each system. Dunant choose a leasehold

ownership system structured so that the leasehold payment would be exactly 20%

times the price the current owner paid for the leasehold. His people called

this system ‘socratic leasehold ownership.’

As we have seen, leasehold ownership systems

that work this way send massive amounts of value to people who improve

properties. People can make a lot of money in ‘pure improvement projects,’

which involve buying leaseholds, improving the underlying properties, then

selling the leaseholds to get the ‘capital gain,’ reflecting the difference

between the sale and purchase price of the leaseholds. The improvers want to do

this because they are greedy. But their interests coincide with the interests

of the Community of Humankind, because each time a leasehold sells for more

money, the leasehold payment that goes to the human race ‘resets’ to a higher

amount, and the income of the human race goes up.

The income of the human race will grow.

In order to understand what must happen now,

you have to have some idea of what it means for income to grow. There are three

general categories of growth in income, with different mathematical properties.

They are:

1. Simple growth

2. Compound growth

3. Exponential growth.

The section in blue shading below explains

them, for people not already familiar with them:

Simple growth, compound growth, and exponential

growth:

Simple growth takes place when an income

grows by a fixed amount of money each year. For example, say you start with

$100 and your income is set to go up by $10 a year every year in the future.

The second year, you get $110, the third you get $120, the fourth you get $130,

and so on. Simple growth is the slowest growth of the three possible ways money could grow.

Compound growth is when

the income goes up by a certain percentage each year. A 10% compound return on a $100 income

stream would provide $110 the second year, but then go up to $121 the third

year. ($121 is 10% more than $110.) It would then go up to $133, $146, $161,

$177, $195, and so on.

Compound growth is significantly faster growth than simple growth.

The above compound growth rates are

compounded annually. This means nothing happens all year long. The very day

that your money is due, the growth is calculated and added. This is called

‘yearly compounding.’ Although income that grows at a yearly compound rate

grows much faster than income that grows at a simple rate, the final kind of

growth is significantly faster than yearly compound growth. It is called

‘exponential growth.’

Generally speaking, events in nature happen

as described above, with nothing happening all year long, and then on one day,

growth takes place. Generally speaking, events in nature are continuous. They

take place all the time. This includes growth. To see this, imagine you are

starting with a small colony of bacteria, consisting of 1 billion cells. Each

cell takes an average of 20 minutes to divide into two cells. If all cells

divided at the exact same time, the population would double every 20 minutes. But the cells are always in a process of dividing,

and the ‘births’ of new baby cells take place constantly. As a result, the

population of the bacteria will increase faster than

indicated above: the population will more than double every 20 minutes.

In the 1700s, Leonhard Euler worked out the math

behind the idea of continuous compounding. He showed that growth at continuous

compounding conformed to certain mathematical laws. He created a set of numbers

that would help people make these calculations, called the ‘natural logarithms.’

(You can find the idea behind natural logarithms explained in any second-year

calculus book, because the ideas of continuous compounding are an integral part

of calculus. Without using calculus, it is pretty difficult to explain the idea

of continuous compounding and natural logarathims. The best explanations I have

found are in the book Euler’s wrote of his letters to one of his pupils, called

‘Letters to a German Princess.’

In the system Dunant set up on Cosmos, the

income of the Community of Humankind in the system Dunant set up will not increase on a regular basis once each year, with nothing happening on

the other 364 days. People will constantly work to improve properties, they

will constantly bequeath new properties, and the Community of Humankind will

have a set amount of money (allocated in the elections, described above) to

purchase freeholds properties and convert them to leaseholds. All of the

processes will take place continuously, so the income of the human race will

grow at a rate reflecting continuous compounding growth. People who deal with

growth rates don’t want to have to use the term ‘continuous compounding growth’

over and over, so they have coined a name to refer to this kind of growth:

exponential growth.

Exponential growth is rather difficult to

calculate, because it involves literally infinite compounding periods. To

calculate by hand or computer would not be possible because it would take you

forever to do the infinite calculations. However, it is possible to use the

shortcuts that Euler devised to make it very easy to do these calculations.

Many people do them in their heads. For example, many people in financial, and

population, and radiation related fields that have to understand growth rates

have learned the ‘rule of 69.’ This rule tells us that, at any continuous

growth rate, populations will double in the number of periods indicated by this

formula “growth rate/0.69. For example, at a rate of 10%, the population will

double in 6.9 years; at 1% it will double in 100 years. Euler calculated a set

of numbers that can be used to calculate exponential growth rates with ease.

These numbers are called the ‘natural logarithms,’ because they are logarithms

(exponents) that tell us what actually happens in the natural world.

The exponential growth rate has a special property

that is best explained using calculus terms. (Don’t worry if you don’t know

calculus, I will explain what the terms mean next.) Specifically, all of the

‘derivatives’ of exponential growth functions are positive.

In calculus, the derivative is a formula for

the ‘rate of change’ of something. A positive derivative means that the ‘rate of change’

is positive. If you have an income function (a formula that indicates your

income) you will want it to have a ‘positive first derivative,’ because that

means that your income is growing.

A positive second

derivative means that the ‘rate of change of the rate of change’ is also

positive. (Note: all these terms have formal definitions in calculus. I am including the

descriptions for people without backgrounds in calculus.) In other words, the

income not only grows each year, it grows be a higher amount each year that passes.

A positive third

derivative means that the rate of growth of the rate of growth of the rate of

growth increases each year that passes. In other words, the income not only

grows each year, and grows more each year that passes, the rate of growth increases by a higher rate each year that passes.

|

Table

|

10.1

|

Exponential Growth

|

|

years

|

simple

|

exponential

|

|

0

|

$100

|

$100

|

|

10

|

$200

|

$272

|

|

20

|

$300

|

$739

|

|

30

|

$400

|

$2,009

|

|

40

|

$500

|

$5,460

|

|

50

|

$600

|

$14,841

|

|

60

|

$700

|

$40,343

|

|

70

|

$800

|

$109,663

|

|

80

|

$900

|

$298,096

|

|

90

|

$1,000

|

$810,308

|

|

100

|

$1,100

|

$2,202,647

|

|

110

|

$1,200

|

$5,987,414

|

|

120

|

$1,300

|

$16,275,479

|

|

130

|

$1,400

|

$44,241,339

|

|

140

|

$1,500

|

$120,260,428

|

|

150

|

$1,600

|

$326,901,737

|

|

160

|

$1,700

|

$888,611,052

|

|

170

|

$1,800

|

$2,415,495,275

|

|

180

|

$1,900

|

$6,565,996,914

|

|

190

|

$2,000

|

$17,848,230,096

|

|

200

|

$2,100

|

$48,516,519,541

|

|

210

|

$2,200

|

$131,881,573,448

|

|

220

|

$2,300

|

$358,491,284,613

|

|

230

|

$2,400

|

$974,480,344,625

|

|

240

|

$2,500

|

$2,648,912,212,984

|

|

250

|

$2,600

|

$7,200,489,933,739

|

The formula for a exponential growth rate

has a special property: all derivatives are positive. It is the only mathematical formula that has this property. This means that it is the

fastest-growing mathematical function possible.

What does this mean in practical terms?

It means that, even if the starting level is very

low, if this ‘one way increase in the income for the human race’ continues long

enough, the human race will eventually wind up getting enough money to make

very real differences in their conditions of existence.

To see that this is true, I want to direct your

attention to the table to the right, that compares that shows simple growth

rates with exponential rates for income. It starts at $100 a year, over a long

period of time, with 10% growth rates:

Note that the numbers in the Exponential column grow at a fantastic

rate, so fast that it is often hard for people who aren’t familiar with math to

understand how such a thing could happen. You can find a great many books that

explain exponential growth if you are interested in this concept or can’t

believe it is true. It is true. It is a mathematical fact that natural growth

processes are exponential and anyone with a computer can calculate them.

(To calculate with a computer, merely use the formula for ‘future

value,’ and fill in the rate, time, and present value into the formula. The

‘help’ file on your computer spreadsheet program will tell you want the terms

mean. The pencil-and-paper formula is ‘FV=PV*e(rt) where FV means

‘future value,’ PV means ‘present value, e means Euler’s constant—the base of

the natural logarithms—r means ‘rate’ and t means ‘time.’)

On Cosmos, Dunant set up the Community of Humankind so that its income

would increase at an exponential rate.

It started relatively small.

But it increased at ever faster rates each year that passed.

Bequests

Many people on Cosmos realized that their world had some serious

problems. They wanted to find a way to help solve these problems. Book One,

Fact Based History, explained the goals of the Earth Henri Dunant, and his

desire to create a corporation like the Community of Humankind. We saw in Book

One that, although the humanitarian organization Dunant created didn’t do what

he wanted it to do, the basic idea behind it inspired a great many people to

donate to it. This organization has become the largest organization of any

kind, with 89 million employees (more than any government on Earth), offices in

every nation (and every disputed region) on Earth, and services that affect

virtually everyone on Earth in some way. (See text box for more information.)

The

Red Cross organizes blood donations, storage, distribution, and transfusions.

People who get blood from the Red Cross don’t pay for it: they get it free. I

was born with a disease that required a complete blood transfusion within hours

after my birth. I got blood because of the Red Cross and would not have lived

otherwise. In 1982 I was stranded when massive floods washed out most of the

roads in Tuscon Arizona. The government appeared to not know what was happening

and didn’t even warn people to not use the roads. The Red Cross anticipated the

flood and set up shelters. I stayed at a shelter after my car washed away and

stranded me. I did not get a bill. No one asked me for money. (The government

sent me a bill for rescuing my car, but my rescue by the Red Cross was free.)

After

Hurricane Katrina took their home in Bridge City Texas, my nieces found a

shelter and told me they were shocked by how organized it was: they got food, a

place to sleep, medical care, and got to use laundry at the shelter to clean

their clothes. Best yet, no one even asked them for money. How could the United

States government do such a good job? They didn’t (the government’s response to

Katrina was legendary for its ineptness). This was Red Cross shelter. When my

aunt drove off the road in Mexico, and tore off the top of her skull as the car

skidded upside down on the road, the Red Cross picked her up, took her to a

clinic, stabilized her, and called me to come and pick her up. She would have

died. She did not get a bill from them. This service is free. This is the kind

of thing Dunant’s company does in our world today.

Cosmos is like Earth in many ways, in that the people there really want to do things to make life better for

others, and would be happy to do this if they had some sort of vehicle that

made this easy to do.

The Community of Humankind was a corporation with an income. Anyone on

Cosmos who knew about the organization and wanted to do so

could register to vote, and voters determined what happened to the income of

the Community of Humankind. They used part of this income to fund research into

the different kinds of societies humans could form. They used part of it to

teach people about the different mode of thinking of the company’s founder, and

the idea of empowering the human race as a whole, rather than of individual nations.

The Community of Humankind was designed to be a tool that the people of Cosmos

could use to make their collective voices head, over the noise of the ‘nations’

and ‘governments’ of their world.

As more people heard about it, more people became involved. If someone

wanted to vote, she merely had to register. Everyone who registered would be

involved, and each of them would have equal rights to determine what happened

to the portion of the bounty of their world that was under the control of the

Community of Humankind. People could see that their opinion mattered and that

they could make a real difference in the world. Once they realized this, they

realized that they could increase the power and rights of future generations by

simply downloading the form, including whatever part of the world they owned in

the parts of the world that benefited the human race.

Time

Passages

Cosmos was a very bountiful planet, about as bountiful as our wonderful

Earth. The total free cash flow of all properties on Cosmos (including all of

the land, farms, forests, factories, mines, corporations, rivers, oceans, and

other ‘properties’ that created value) started out at about $40 trillion a

year. (In other words, equivalent in purchasing power to $40 trillion in Earth

United States dollars.)

After the first donations, the Community of Humankind had control over

so little of this money that it sound silly to represent it as a percentage:

the total income the first year was a mere $40,000,000 a year. (This is about

the yearly income of the today, a humanitarian organization dedicated to

‘advancing the cause of interior design.) This was only 1/10000th of

1% of the total free cash flow of the planet. But although $40 million may be

small compared to the total free money available, it is a large amount of money

in nominal terms. It helped a lot of people.

By the time a 15 years had passed, the income of the Community of

Humankind had increased to $2 billion a year. This is still small relative to

the total free wealth of Cosmos (about 1/20th of 1%) but is enough

to make a big difference in important variables in the world. (It is roughly

equal to the 2015 income of the United States government.) By this time, nearly

everyone on Cosmos knew about the system, and participated in its elections.

The human race began to use the income and power of the Community of

Humankind as a tool to induce national governments to conform to certain

standards. For example, the people of Cosmos realized that their governments

really didn’t do good jobs in certain areas, because of their focus on politics

and military power. They didn’t really deal with disaster very well, they

didn’t have any comprehensive policy to deal with war refugees, they didn’t

have any organized system to adjudicate disputes between governments, for a few

examples. The Community of Humankind could take on these roles, relieving the

governments of nations of any need to worry about them. But, in return for

being relieved of these costs, the governments of the nations would have to

sign documents agreeing to protect certain rights.

On Earth, Dunant set up the Geneva Accords, a system that would give

all nations access to free medical care (provided by the Red Cross), in

exchange for signing the accords and agreeing to certain rules of war. The

Earth Dunant set up the World Court, and made attempts to set up similar

provisions which would provide certain services for everyone, in return for

agreements to abide by the decisions of the court. (Dunant was just about broke

by the time he set up this system, due to his legal fees defending his vision

for the Red Cross. As a result, his attempts didn’t work out.) By the time 15

years had passed, the Community of Humankind was a very large and

well-respected organization. It wanted nations to be tools to create

cooperation so there could be more value for everyone, rather than independent

sovereign entities with the authority to take wealth from their people and use

it to build weapons to force other people of their world to adhere to the edicts

of the governments.

Over time, power shifted. The power of the Community of Humankind

increased while the power of nations decreased.

On the road map of possible societies, the society of Cosmos had

changed. It was not on the extreme bottom line anymore. Nations still had a

great deal of power and wealth. But the members of the human race had a tool

they could use to transfer some

decisions from ‘nations’ to the human race as a whole. The term ‘sovereignty’

means ‘unlimited rights.’ Nations no longer had sovereignty. They no longer had

sovereign law societies on Cosmos.

It took more than a decade to get from ‘the extreme bottom line’ on the

road map of possible societies to ‘a line that is a tiny, tiny bit above the extreme bottom line.’ In 15

years, the human race had moved from controlling 0% of the bounty of Cosmos to

1/20th of 1%. This is such a small difference that you wouldn’t even

be able to tell the difference on the road map of possible societies between

the two lines, they would be so close to each other. Relative to what is

possible, the people haven’t changed very much. But in absolute terms, the

human race had enormous powers. At 1/20th of 1% of the bounty of

their world, they controlled $20 billion a year in wealth. Although 1/20th

of 1% is a tiny percentage, the actual amount of money they got, $20 billion a

year, was high enough to make a huge difference in the way the world worked.

Since this money was controlled by the human race as a whole. The human race had certain goals and common needs

that the nations of the world

weren’t able to meet. Before the Community of Humankind existed, the people of

Cosmos didn’t have any kinds of tools they could use to advance these

interests.

Now they did.

Having this tool also gave them a forum. There is an old expression:

money talks, bullshit walks. Before they had a tool, people could talk all they

wanted about how messed up their system was and what ‘they’ (the mysterious

unspecified ‘they’ who supposedly looks out for the interests of the common

people) should do about it. This was, as the saying goes, nothing but bullshit:

It had no value because there was no value to back it up. Now that they had the

tool, they had something which ‘talked:’ money. They could talk with their money and make a real

difference in the world.

Sustainability

By the time 15 years had passed, only about

1/20th of 1% of the free wealth of Cosmos went to the human race.

This is a tiny percentage.

The laws of exponential growth kept

operating. These are mechanical, mathematical laws that don’t have anything to

do with feelings or emotions. When the Cosmos Dunant set up the Community of

Humankind, he wanted to change the world. He knew that he couldn’t do this all

at once, and transform the world in a single day. It would take time. He wasn’t

trying to make a name for himself or gain power or control, he was trying to do

something that would really work. He wanted to give the human race some power, even if it was such an

infinitesimally small amount of power that it wouldn’t be noticed. This kind of

change could make a difference if it were set up so that the power of the human race would grow over time.

Each time the power of the human race grows,

the society of Cosmos moves upward

in the range of possible societies on the road map of possible societies. Seen

from the perspective of someone living on Cosmos, the change would be so slow

as to be imperceptible. However, an outsider, say someone watching Cosmos from

outer space, who had any kind of reasonably long time horizon, would begin to

see significant and important transformations in the way the societies of

Cosmos worked.

One important change would involve

incentives and responses to incentives. Movement upward in the chart causes

money that had gone to pay people

to destroy and create conflict now no longer goes to these people and is not

tied to destruction and conflict anymore. As the rewards of conflict and

destruction fall, the incentives

to destroy and make war get weaker.

Incentives matter.

Perhaps many of the people who had been

involved in war industries or destructive resource management would have

preferred to have had a peaceful and healthy world for their children. But in

the sovereign law societies, they weren’t in a position to choose: they needed

money, they could get money by participating in the military industrial

complex, so they had to participate. As the rewards that flow to destroyers and

murderers wane, many of these people are not going to make enough money participating in destruction

to justify the damage they know their participation will case. (As the rewards

of destruction fall, the people who control wealth or want to build weapons

can’t afford to pay as high of wages to people who help them do this.) At the

same time, the rewards that come from constructive behaviors increase. People

can make more money creating value and less money destroying it.

The amounts

of money involved, so far, are not huge. But incentives matter, and even small

changes in incentives lead to changes in behavior, particularly when we look at

large groups of people. Rates of destruction fall. Rates of creation of value

increase.

The minimum condition that must be met to

have sustainability would be for the rates of destruction of things of real

value to be no greater than the rates of creation of real value. A society can

create more value than it destroys forever. Since ‘value’ is defined ‘good for humans,’ more value

created means more good things for humans to enjoy. There is no point at which

life will get ‘too good to continue to survive.’ Life can keep getting better

forever, so any society that creates more value than it destroys is

sustainable. The minimum

conditions needed for sustainability involve destroying no more value (of all

kinds) than is created. All societies that destroy more value than they destroy

are not sustainable.

If we continue moving upward in the range of

possible societies, we will eventually get to the minimum conditions needed for

sustainability.

The

realities of the Minimally Sustainable Societies

The people of Cosmos are raised in entities called ‘nations.’ The

nations of the minimally sustainable societies are not so far removed from the

nations of sovereign law societies as to change their nature. The people in the

governments of Cosmos still think of war as a reality of existence and still

believe that they will absolutely need children to grow up with the mindset

necessary for organized mass murder and the rape of the world’s resources

needed to keep the war machines operating. They still try their best to implant

the necessary mindset in children. The adults in this altered society were

generally raised in school systems that were designed to implant these beliefs.

A

reminder:

Book

One of this series, explains the way the Earth got to the place it is as of

2016. Here is a quick recap:

The first ‘joint stock’ corporation, East India Company (British) was

formed in 1600. The first corporation with stock certificates (which allowed owners to be anonymous, because

the owners names weren’t recorded anywhere) was the Dutch East India Company,

incorporated in 1602. In the next few years, several corporations were formed

and given ownership of roughly half of North America. (The Virginia Company and

subsidiaries, the Massachussetes Bay Company, the Company of New France, and

the French West India Company, to name a few.) These corporations ran North

America independent of the rule of national governments until 1763, when a

treaty signed by all major powers granted the eastern half of North America to

England.

King

George III issued the ‘proclamation of 1763 which stated that, now that America

was a part of England, it would have to adopt the laws and practices of

England. This included honoring contracts, which would require returning all land

stolen from the American races by the giant corporations (The Ohio Company,

controlled by the Washington family, the Loyal Land Company, owned by

Jefferson, for example.) It included freeing all slaves (about ¾ of the people

of America were ether black slaves (property slaves) or white slaves

(indentured servants) and granting all former slaves and American races equal

rights and equal votes in government.

To

prevent these changes from actually taken place, ‘independence advocates,’ led

by George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Samuel Adams (all heads of giant

corporations) organized a coup d’eat and managed to take over control of the

lands. They passed several laws designed to prevent the desired changes from

taking place.

On Earth today, corporations do the exact same things. They have gained

autonomy, meaning the ability to act independently of governments (if a

corporation doesn’t like the rules of the nation where it is incorporated, it

can move its ‘nation of incorporation’ in a very short time—a matter of seconds

for small corporations, and days for large ones—allowing it to create its own

rules). Although corporations can do these things, they generally don’t, for a

simple reason: the corporations basically control

the governments through their lobbies.

Virtually all legislation today is written by lobbies, not elected officials. (To verify, look up

the text of any modern law and read it. Do you really think that any of the

people elevated to office could possibly have enough background in the area the

law deals with to write such a law? Then consider the effects of the law. Do you think it is an accident that the ‘clean air act’ increases the subsidies that go to industries that pollute the air?

The people who wrote the laws wanted this to happen; the realities of party

politics forced politicians to support the bills without any need for the

politicians to even read the

bills, let alone understand them.)

The system the United States created in the late

1700s became a model that the rest of the world had to follow in order to

remain competitive militarily. The United States system is based on rulings

like —explained in detail in Book One, —which accepts that corporations are

persons under the law, with rights to protection of their freedoms of speech

(the freedom to bribe politicians, something that the Supreme Court rulings

accept took place in the incidents that led to the Fletcher V Peck ruling). It

grants them protection of their contracts (even if the contracts were obtained

by fraud, bribery, theft, and involved the sales of properties that the sellers

did not own and had no right to sell, all of which were the case in the events

that led to the Fletcher V Peck ruling).

Although the specific details started in the United

States, the rest of the world had to adopt the underlying model to have

corporations that would produce efficiently enough to keep them connotative in

war. As a result, all ‘advanced’ or ‘developed’ nations have such rulings, and

corporations have roughly the same powers in all of them.

Remember that the Community of Humankind is not a national organization, formed in a single

nation to advance the interests of that nation. In fact, the Community of

Humankind is a global corporation that acts totally independently of the governments

of the world.

The Community of Humankind is independent

of nations. It is an autonomous

corporation, an entity that the leaders of war-driven societies of Cosmos had

been forced to build enough war supplies to compete in their wars. Once this

organization began operating, people began to realize that they had power and

authority that was independent of

the organizations they had been raised to call ‘their nations.’ Theys had flows

of wealth that depended on the productivity of the parts of the world and other

productive assets that had been

purchased by or donated to the Community of Humankind; the more assets n this

category, the more power and control the human race had and, by extinction, the

less power and control the nations of the world had.

The people of Cosmos could increase the power and control the human

race had, relative to the power and control that the entities called ‘nations’

had, by several mechanisms. (They could vote to use some of the revenue of the

human race to expand the system, they could donate their time, effort,

resources, skills, money, land rights and other capital to the cause, or they

could generate bequests that would cause their estates to sell socratic

leasehold ownership rights to the land and give the money to their heirs,

rather than giving freehold rights away after they died, for a few examples.)

People would realize that they had control over their destiny. They would

realize that the story that nations were in charge of everything was simply not

true.

As time passed, more and more people came to realize that the human

race has real control and power to affect its destiny. They would be able to

project the trends that give the human race power into the future; they would

realize that eventually the human race would have more power and control over

important realities of earth existence than the nations of the world. If the

human race is in charge, the interest of the human race matter, not the

interest of nations. The rulers of nations are behind war and conflict; they

are behind the propaganda that induces children to think that we must fight,

kill, and die for these entities, they are behind the laws that subsidize the

destruction of the human race and prevent the majority from sharing in the

wealth of the world, forcing them to care more about the amount of jobs that

exist in the world than they care about the very existence of the planet.

The human race as a whole does not benefit from any of these things. As

we move toward a situation where the human race has power and authority, the

interests of the human race will matter more and more and the interests of

other entities, including nations and organized religions, will matter less and

less.

First,

vote.

In sovereign law societies, elections are generally meaningless, as the

people have no power to alter any important realities of their existence. (They

can’t vote on whether nations will exist, for example, or alter any fundamental

fixed realities held in ‘constitutions.’ They can’t prevent schools from teaching

patriotism in the elections, divert money from government programs that pay for

nuclear bombs to programs that bring real benefits to the people of the world,

or change the way ownership or ownablity of productive assets works (either in

society as a whole or in the land called ‘their nation’).

When the Community of Humankind voted, the votes meant something

important. Each vote represented some share of the wealth the world created.

Each vote transferred some of this wealth to programs the people of the world

had created which were designed to meet some need or advance some goal of the

human race as a whole. If you lived on Cosmos, you could watch the numbers in

the accounts: when you transfer $100 to ‘the child welfare fund,’ you would see

the bank balance of the human race for ‘unallocated funds’ fall by $100 and see

the bank balance for the ‘child welfare fund’ increase by $100. If you have

1,000 votes, each worth $100, you could make a substantial difference in the

way the world works with your votes.

In his book 1984, Orwell commented many times on whether democracy

really could exist in a society. We have seen that no sovereign law society can

be a true democracy, because of the practical requirements of war: Victory in

war is essential for nations to exist and the decisions needed for war can’t be

made effectively in elections. (Most people would rather have better roads than

more aircraft carriers and ICBMs. If some nations made these decisions in

elections and others didn’t, the ones with elections would not have enough

weapons to defend themselves against the nations without elections and would be

conquered.)

It is true that democracy can’t exist in societies built on the belief

that invisible superbeing have given away parts of planets to people who own

them totally (or that people who go through the rituals needed to claim the

land are the absolute owners). But these are not the only kinds of societies

that are possible. Others can exist that are capable of supporting true

democracy. Socratic leasehold ownership societies are fully compatible with

true democracy. In fact, they work best if the people make the decsions about

allocation of all unearned wealth (the basic productivity of the land).

Growth

in Power of the People

All of the people of Cosmos had a right to vote in the global

elections. If they wanted, they could use the wealth they distributed to

benefit them, personally, providing services for themselves and distributing

all of the rest of the money to the people as cash basic incomes. But if even a

single person on Cosmos cared about the future of the human race, she could

cast one, more, or all of her votes for projects that would increase the power

and authority of the human race going forward. These projects could work to provide

cash subsidies to property owners who agree to bequeath their properties to the

Community of Humankind, after they die, to be sold with socratic leasehold

ownership (instead of with freehold ownership). True, the properties would not

sell for as high of prices with socratic leasehold ownership as with freehold

ownership.

A great many people on Cosmos wanted their properties to benefit both

their heirs and all future generations of humans. Before the Community of

Humankind was created, they didn’t have any real way to do this. After it came

to exist, they could download a form from the internet, fill it out, have it

notarized and sent back to the Community of Humankind administrative offices.

When these people passed, the properties would go to the Community of

Humankind, which would then sell socratic leasehold ownerships on the property

and transfer all funds obtained to the designated beneficiaries of the

benefactors.

With the right kind of program, this system can be very beneficial to

estate planners. In some nations on Cosmos, estates pay out more than 90% of

the money value of the inheritance on lawyers, probate, taxes, and fees. Owners

would realize that their heirs really wouldn’t get much money from the

properties if they went through probate, they would be able to give more to

their heirs if they went through the Community of Humankind program, with much

more rapid progress and much less chance for disputes among heirs. The system

the Community of Humankind set up on Cosmos was very easy: a single form,

signed, notarized, and sent in by mail, and everything was done. The leasehold

to the property would be sold within 30 days, and their heirs would get the

money the next day. Many times, people could actually leave more money to their heirs by going through

the system at the Community of Humankind, than by bequeathing the property to

their heirs (who often would have to sell anyway to pay legal fees, probate

costs, and estate taxes).

As on Earth, people of Cosmos cared about the world and wanted to make

it better. They gave to many charities. As time passed, the Community of

Humankind became a kind of ‘charity of charities.’ If the people of Cosmos wanted more to go to a project like ‘Habitat

for the People of Cosmos,’ but had no money ‘of their own’ to give to the

charity, they could log on to the website of the Community of Humankind and

give money that belonged to the human race to the ‘Habitat for the People of

Cosmos’ or ‘Doctors without Borders.’

People giving to charities often have hard

decisions. Not all charities are honest. Some are shams. Dunant set up the

Community of Humankind to be totally transparent. Every single penny of income

and expenses for the humanitarian organization was recorded on accounting forms

that anyone could verify and audit (using the procedures explained in Chapter

11 of Book One.) People who wanted to give to other

charities would not know exactly what would happen to the revenues from their

bequests after they had passed away. (Dunant wanted to create a system where

the people had authority over the Red Cross to make decisions. He was

overruled. The executive committee of the Red Cross makes these decisions, in

meetings that the donors of the corporate can’t attend.) For most charities,

people have no way to tell if the charity is giving money to organizations

designed for terrorism (like national governments, which use the money to build