Chapter Two: The Foundation of Society

The physical world is the ultimate source of all of the food we eat and all the other physical things we need to keep us alive. It provides our food, shelter, the materials we use to build our tools, shelter, fires, places to build, places to live, our water, our air, and everything we need to keep us alive and make our lives better. The way we choose to interact with the physical world determines who gets these things what they have to do to get them.

If you can get food, shelter, or other things the world provides by acting certain ways, you have incentives to act those ways. You can think of an incentive as a kind of invisible hand pulling you toward a goal:

You see food on a tree and you are hungry. You feel psychological pressure to try to get the food. You can’t just say an incantation and get it: you need to do certain things. But what? The incentive pressures you to figure out what. You must figure it out and practice it. If it works, you will get the reward of the food. If not, you will remain hungry.

Humans, like all other living things with physical needs, must react to incentives. If you decide you are going to ignore the pressure to get food, eventually you will starve to death. Some animals can meet all their needs without help from their peers. But humans are not in this category. We need to organize ourselves in some way to help us meet our needs. This means that we will have to work together to create rules that determine exactly what things people will have to do to get food and other necessities.

Societies with 0% ownability societies have entirely different rules about who gets food and other necessities and what they have to do with them than societies built on 100% ownablity. In 0% ownability societies, no one owns or can own the land. If no one owns the land, no one owns its bounty. In such societies, the people will have to make some sort of decisions about what to do with this bounty. We would expect them to share it in some way. Most likely, they would not want people who act in ways that harm others (say thieves and murderers) to have the same share as responsible people. Most likely, they would share it in some way that gave responsible people more and irresponsible people less. If people are rewarded for acting certain ways, they have incentives to learn the appropriate behaviors (the right way to act to get the rewards) and act that way. These societies naturally reward responsible behaviors, so they create incentives that naturally encourage responsible behaviors.

Unfortunately, 0% ownability societies don’t accept that people can own wealth that flows from the land even if those people are solely responsible for creating certain flows of wealth. For example, if you improve land in a 0% ownability society, you have no natural rights to the increased wealth the land produced due to your effort. As a result, these societies have no incentive systems that encourage people to use their skills, time, talents, resources, money, and other things that are collectively called ‘capital’ in ways that lead to improvements and advancement of technology. 0% ownability societies have

Societies that accept 100% ownability (sovereign law societies) accept that the land is owned and the owners get everything it produces, including its bounty. People who don’t own must work for people with rights to food and other necessities, or they will not be able to get the necessities of life and will die. The owners have powerful incentives to try to organize themselves into groups (nations) so that they can build a collective defense for their land and, perhaps, be able to conquer still more land. They need a lot of people who work for them to extract the resources needed for weapons, to manufacture the weapons, and to join the military establishments that actually use these weapons against others. People are offered rewards in the form of money if they do things that lead to the extraction of resources or military conflict. If people are rewarded for acting certain ways, they have incentives to learn the appropriate behaviors (the right way to act to get the rewards) and act accordingly. These societies naturally reward destructive behaviors, so they create incentives that naturally encourage destructive behaviors.

Book One described an example society based on an intermediate relationship with the land. In that society, our people didn’t try to solve the problem of whether parts of planets were ownable before we organized our societies. We decided this was a complicated question that we wanted time to solve. Until we had the answer, we decided to build our societies on some other factor. In the example society, we decided that we would accept that the dominant animals on the earth got first claim on the good things the world produces and contains. We could therefore make rules regarding the use of the land if we wanted, and no other animal could prevent these rules from being the rules of existence for this planet. We decided we were the lords of the land.

We could have simply guessed about the best way to interact with our land, perhaps praying to whatever invisible superbeings any of our people believed existed for guidance. If we didn’t have a professional in our group who had studied the different options and knew how they worked, we may have guessed. But we had an expert in our group who knew about all the options.

Terry told us that she understood a science that was devoted to studying the different ways people could interact with ‘property,’ including ‘real property,’ the common name for ‘parts of the world that are considered ownable.’ As part of this science, she had studied the different ways that landlords could deal with their properties. She knew how all of them worked. She told us that the science is fairly complex and technical and she didn’t want to try to explain it all to everyone before we did anything. She asked us to allow her to make a presentation. In this presentation, she explained the specific option she had used her science to select as the one most suitable for the needs of the current landlords of the world, the members of the human race.

Before we consider the scientific options, let’s review a little so we can understand why science is not needed to understand some of the options on the Road Map, particularly societies built on the two extreme methods of interacting with the land, natural law and sovereign law.

Extreme Societies

It is possible to build societies without even using the higher intellectual powers and reasoning skills of the human race. We can start with nothing but emotions, we can think about the emotions and analyze which one feels right, and we can then claim that we want whatever feels like it is what we should have, then put that one in place.

Consider this thought experiment:

Think about whether the planet we live on and its parts are ownable, and whether people or groups of people can own. If you start with the right perspective or guidance, you may be inclined to believe this does feel right. For example, we appear to own our own bodies, we appear to own our free will. We clearly have the ability to make claims to own and then create structures that allow us to enforce these claims.

Many people have thought through this idea. Some of them accept the idea of a higher power and some don’t. Those who accept the idea of a higher power (some sort of entity with the ability to think which has more authority here on earth than we have), often justify their feelings that the planet is ownable by claiming that it must be the will of the higher power that we own. The higher power allows the stronger and more aggressive people to control the weaker and less aggressive, so He must want the stronger and more aggressive to control the weaker. This must be a part of some natural order that was a part of existence before humans even evolved.

Different drugs tend to affect our emotions different ways. If you want assistance feeling the emotions that help people believe that aggression and physical domination grant people rights to parts of the world, alcohol appears to have this effect on most people. I have talked to many people who seem absolutely sure of this belief set when they are drunk. Many of them openly state they will fight anyone who says they are wrong, at least for the time they are under the influence.

You don’t have to use any math or science to determine how you feel about something. If you want to build societies on feelings, you can ignore science, ignore math, and, for that matter, ignore physical reality. (Many people who accept feeling-based philosophies aggressively deny hard physical evidence if it contradicts their beliefs. I have known people who insist the Old Testament—accepted by Jews, Moslems, and Christians—give an accurate picture of creation and all of the evidence that backs evolution or shows anything in existence is more than 6,000 years old was created and then planted here by a jealous God to test His follower’s faith.)

You don’t have to know any math to analyze your feelings, or even understand what the term ‘science’ means. You don’t have to understand the mechanical elements of human modes of interactions, or the different ways the different mechanical structures that help us meet our needs can interact with each other. You don’t have to understand the nature of the incentives, the source of the incentives, or anything at all to do with flows of value that create incentives. You can just take drugs and analyze your feelings. If you feelings tell you that the world is ownable, and the strongest and most aggressive are the owners, you can then say that this is your belief, and you will not accept any analysis of society that doesn’t start with this belief.

You may also use your feelings to come up with an entirely different set of beliefs.

For example, imagine you are out in a beautiful natural setting, on a clear, moonless night, away from noises and distractions of the 21st century world. You look up at the sky and think of all the stars, planets, and endless galaxies full of stars and planets. Think about how large the universe is and now tiny and insignificant this tiny solar system is by comparison. Think about how whatever parts of nature you think are attractive and appealing, then think about clear-cutting, strip mining, nuclear bomb testing, and all of the other human activities people claim they have absolute rights to do, because the parts of the planet belong to them or their ‘nation’ (which has given them permission to do these things).

Again, drugs can help people feel things that they can decide are foundations for their beliefs. People on marijuana often tell me that they feel peace and harmony are good things, and concepts that disturb peace and harmony, including the idea of ownability of this wonderful planet, just don’t feel right. They say that this world is more like our mother than our property, and we need to take care of it or it will destroy us.

Think about this until you start to feel some emotions.

If, after thinking about the ownability of the world, you decide it just doesn’t feel right, you might think about what kind of relationship between the human race and the world does evoke satisfying emotions. You might think about the incredible beauty of the natural world and how it feels to be on such a wonderful planet. You may think about the idea of the human race existing just to keep the world in this beautiful condition.

Many people have thought about such things until they felt emotions. In many cases, the people decided that it simply felt right to accept that the world is above us all and not our servant at all, but our master. They thought it felt right to accept that the laws of nature are above the laws of humans and humans should respect the laws of nature above all other laws. If enough people in a given area feel this same way, they can organize their existence around this belief. They can create rules that require others to act in accordance with the beliefs, to take care of the world, and rules that prevent any person or group from having any rights that might be considered to be owned or ownable.

Again, people don’t need any math or science to build these societies.

People can understand the principles behind and build the extreme societies without understanding even the most basic elements of science or mathematics. All they have to do is be able to feel emotions.

Creating Intermediate Societies

We don’t need intellect to build the extreme societies. They can be built entirely on beliefs. People can start with guesses about things for which they have no real evidence or proof. They can then build structure around these beliefs. If they get to a place where things don’t fit together properly (and this is bound to happen, since the structures are not built on a logical analysis of anything), they can make guesses about what feels right to them. Some people will feel it is right that THEY be in charge and make the rules. From time to time, the people who feel this way will be in a position to persuade, coerce, or otherwise induce others to accept their rules. They can make rules based on their feelings and beliefs.

The two extreme societies are amenable to this kind of analysis. People who are guessing about whether parts of planets are ownable by mortal beings like humans are likely to guess that either we do own or we don’t own. All or nothing are both likely guesses. They are not likely to guess that humans naturally own certain rights but do not own certain other rights. For example, they aren’t likely to guess that some higher power wants them to set up a leasehold ownership system like the one described in Book One, which allows people to buy and own rights to improve the world, to keep increased flows of value due to their improvements for whatever period they wish, but which leave the rights to destroy the land and rights to certain unearned flows of value to be unowned and under the control of the human race as a whole. People making guesses about philosophical issues will not be likely to guess that things are very complicated. They will keep their guesses simple: either whatever forces or powers that determine what should happen in the world want us to own or don’t want us to own. Once they have decided what they believe, they will build societies around these beliefs. We will then end up with either natural law societies or sovereign law societies.

In earth history, people appeared to have made one guess for a long period of time everywhere, guessing that the world was not ownable by human beings. During this time, people formed societies around these beliefs: 0% ownability societies. Then, in Afro-Eurasia, a group changed their belief system and accepted that humans were owners of the world (or could be, provided they went through certain ceremonies and rituals). They formed 100% ownability societies.

Intermediate societies are derived societies, created by mixing and matching the various elements of the extreme societies together. To form these intermediate societies, we must analyze several different variables and relationships between variables, and figure out how they can fit together. We use different parts of our brains to understand and compare complex relationships between variables than we use to analyze our emotions.

To even accept that the intellect-based societies are even possible, we have to use our minds in ways that leave emotions out of the picture.

After we have accepted they are possible, we have to use large amounts of intellectual effort to figure out how the variables we can control relate to each other and the extreme societies, and how people would live in these societies if they existed. Intermediate societies can’t be built on beliefs. To build them, we must understand certain technical relationships between the way people think, the decisions they make, and the forces that influence these decisions. In some cases, the tools people use to make decisions are highly technical. Our feelings can’t help us solve technical problems. We need technical skills.

Property Management

Many people in our world today work in the field of property management. This field is about making practical decisions about land use on a day-to-day basis. The people who make these decisions are generally called ‘landlords.’ Landlords may or may not be owners. Good land management decisions are the same whether or not the landlords are owners. In other words, we can basically ignore the issue of ownership of the land when making land management decisions. The best way to manage land is the same no matter who owns the land.

One way to manage property is to simply rent it out.

If you rent property out, you are actually just paying someone to operate it.

To see this, let’s consider what we did with Kathy and the Pastland Farm when we first arrived in the past. The farm produced $3.15 million worth of rice a year. We hired Kathy for $50,000 a year to run it. We agreed to reimburse her expenses, which worked out to $700,000 a year. She took care of the paper work, selling the rice (trading it for money), and paying all suppliers and workers for their services and labor; this includes the $50,000 she paid herself. After she was done with all this, she had $2.4 million left over; she turned this money over to her landlord, the human race.

Technically, she was a hired employee. But we could have created the exact same flows of value by simply renting the farm to her for $2.4 million a year, and letting her keep everything above that.

This is an extreme way of managing property. It gives the people making day-to-day decisions over the land no ownership interest in the property at all. The managers can ‘add in’ elements of ownership if they want create different incentives for the people who make day-to-day decisions over the land. They can do this by using leasehold ownership rather than pure rental. Leasehold ownership systems are basically partially rental and partially ownership. One easy way to do this would be through leasehold ownership. Rather than selling all rights to the property, the landlords create permission slips that offer certain rights to the property for sale. The buyers of these permission slips will then own certain rights to the property. If the property produces a free cash flow (as the Pastland Farm does), the landlords may set up the leasehold ownership system so that the people making day-to-day decisions over the land must pay some or all of this free money out as leasehold payments to the landlords: the landlords will get (some or all of) the free money, rather than the people making day-to-day decisions over the land.

The Price Leasehold Payment Ratio

Leasehold ownership is a tool. Leasehold ownership is an adjustable tool; we can adjust several mechanical variables to make it work differently. By changing one specific ‘adjustment’ on this tool, we can alter the way we interact with the physical world over a wide range, creating any ‘degree of ownability’ from 0% to 100%.

The inside scale on the left side of the Road Map is marked ‘The Price Leasehold Payment Ratio.’ The numbers on the ‘Price Leasehold Payment Ratio’ scale are basically numbers that we can ‘set’ on the leasehold ownership ‘tool’ to make it do different things.

We have looked at one possible way to set up leasehold ownership, called ‘socratic leasehold ownership.’ In socratic leasehold ownership systems, people bid on leasehold titles by offering prices for the titles, but knowing that these price will determine the leasehold payment they will have to make each year: The yearly leasehold payment is always exactly 20% times the price.

For each dollar of price they offered, buyers are offering their landlords 20¢ per year as leasehold payments.

For each $1 million offered as a price, buyers offer $200,000 to the landlords of the planet each year as leasehold payments. If you refer to the Road Map ( to Road Map) you will see that the horizontal line marked ‘Socratic leasehold ownership societies here’ intersects the price/leasehold payment ratio at exactly 1:20%.

In the other leasehold ownership systems, the landlords set a different ratio between the price and leasehold payment. We then sell the leasehold in a market. People who want to control the property must buy the rights to do so in this market. They must offer both a price (one-time payment to the landlords) and a leasehold payment (yearly payment to the landlords).

The socratic leasehold ownership system provides an example. In that system the leasehold payment had to be exactly 20% times the price, or the price had to be exactly 5 times the leasehold payment. (This is saying the same thing two different ways.) In the examples in Book Two, the people involved (Kathy, the buyer, and Terry, the investor who would provide the money for the price) did the calculations to come up with an affordable price that had this relationship. After the first sale, people who wanted to buy the leasehold title had to buy it in a market which was structured so that they had to bid both a price and leasehold payment, and the price was exactly 5 times the leasehold payment. The landlords got certain advantages from this particular relationship, as you saw.

There are an infinite number of different possible ratios that the landlords could choose, each of which leads to a different kind of property control. The landlords could choose an extreme ratio of 0:1, meaning that the price is zero times the leasehold payment. Any number times zero is zero so the ‘price’ is therefore always zero and whoever offers the highest rent (leasehold payment, paid in this case as a rent) will win. This leads to leasehold ownership that looks and works just like pure rental.

The landlords could choose the opposite extreme of 1:0, meaning that the leasehold payment is zero times the price. Any number times zero is zero so the leasehold payment is therefore always zero and whoever offers the highest price will win all rights to use the property without ever paying the landlords anything after the price; his leads to leasehold ownership that looks and works just like a freehold system. Intermediate ratios, like the 5:1 ratio of Socratic leasehold ownership, lead to intermediate systems. (Again: don’t worry if this makes no sense to you; to really understand it you will need a lot of background information; Book Three presents all the necessary background and details.)

The Road Map has a scale of numbers on the inside left vertical (up-down) axis labeled ‘price : leasehold payment ratio here.’

Leasehold ownership systems are created by landlords. If we accept that the members of the human race are the dominant animals on earth and therefore the lords of the land, we can accept that we have the ability and right to use this tool. The tool is adjustable. If we decide we want to use it, we can then decide how we want to ‘set’ the adjustment on it.

We can ‘adjust’ it so that the property control system is identical to a total non-ownership system, as natural law societies have. We can also adjust it so the property control is almost, but not quite, identical to the control system in natural law societies. If we decide to use such a system as a foundation for our societies, we will end up with societies that work almost identically to natural law societies, but just have a few tiny characteristics of societies that accept ownability.

We can adjust it so that the property control system is identical to a total freehold ownership system, as sovereign law societies have. We can also adjust it so that the property control system is almost identical to a total freehold ownership system, as sovereign law societies have, but not quite identical. If we use such a system as a foundation for our societies, we will end up with societies that work almost identically to sovereign law societies, with almost all of the incentives of these societies, but have a few of the characteristics of natural law societies mixed in.

We can also adjust it to create property control systems that are totally unlike the property control systems in the extreme societies. For example, we can adjust it to a 5:1 ratio (see sidebar for more information), creating a form of leasehold ownership I call ‘Socratic leasehold ownership.’ This was the foundation for the example society explained in chapters 5-8. As we saw, the Socratic leasehold ownership society was a kind of hybrid society, with some characteristics of natural law societies mixed together with some characteristics of sovereign law societies.

Don’t worry about the numbers, mechanicals, or technical details here. The next few chapters explain all of them. All I am trying to explain here is the general idea behind the scales of the Road Map and the basic relationships between the societies on the Road Map.

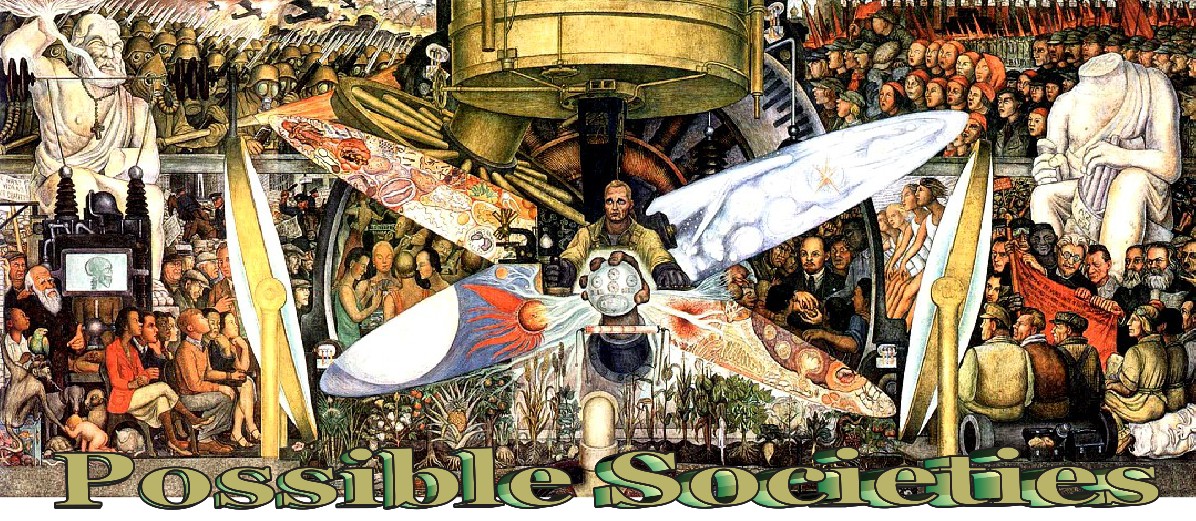

Societies on the very top line of the Road Map are natural law societies. These societies have existed on earth. Many people have lived in these societies and wrote about their experiences; we have many records of interactions between these societies and sovereign law societies. You can find a great many of these descriptions and records in Volume One, a great many more in the ‘References’ section of the Possible Societies website, and enough references to keep you reading for the rest of your life on the internet, if you start looking up the original materials referenced in the books in the references section.

We know how natural law societies work.

Societies very close to natural law societies in on the Road Map will distribute value very similarly to natural law societies so they will have virtually the same incentives. We would expect societies very close to natural law societies to work almost identically to natural law societies.

Societies on the very bottom line of the Road Map are sovereign law societies. We also know how these societies work, because we all live in them. Societies very close to the bottom of the Road Map have flows of value and incentives very similar to the flows of value and incentives of sovereign law societies. These societies will look and work very similarly to sovereign law societies.

The middle line of the Road Map is marked ‘Socratic leasehold ownership societies here.’ We have looked at one example of a Socratic leasehold ownership society and followed it for a few generations to see how it evolved. As we saw, Socratic leasehold ownership societies are hybrids with some characteristics of natural law societies and some characteristics of sovereign law societies.

Socratic leasehold ownership societies basically split the range of possible societies into two halves. One half, the upper half, includes all societies between natural law societies and Socratic leasehold ownership societies. These societies would be expected to be hybrids that mix the characteristics of the two ‘parent’ societies. The lower half includes all societies between Socratic leasehold ownership societies and sovereign law societies. These societies would also mix the characteristics of the two parent societies.

Incentives

If you draw a horizontal line anywhere on the map, you would be drawing a line joining all societies built on the same interaction between the human race and the world. The way we interact with the world determines the inherent incentives of the societies, so all societies on that same line would have the same inherent incentives. (They may have different governments and therefore different man-made incentives, but the inherent incentives will all be the same.) A set of scales on the right side of the Road Map indicates the strength of two very important kinds of incentives.

Constructive incentives

Some of societies distribute value in ways that reward the creation of value. They reward people who improve land so its’ bounty increases (in other words, its free cash flow increases). They work to send money rewards to people and companies that create structures that turn free raw materials (like iron, calcium, silicon, and aluminum) into valuable outputs (like steel, glass, concrete, solar photoelectric panels, appliances, high-rise luxury skyscrapers, and high speed magnetically levitated trains). I use the term ‘constructive incentives’ to refer to incentives that reward behaviors that lead to more creation of value over time.

Destructive Incentives

Other societies have incentives that reward people who create conflict, build weapons, destroy lives and property, devastate the environment, and do other things that make the world a worse place for the people in it. I call these incentives ‘destructive incentives.’

Many of the societies we will visit in the journey through possible societies have both sets of incentives. They will have invisible hands pushing people to do things that make the world better (create value) and also to do things that make the world worse (destroy value). These incentives come from flows of value that we can measure in money. If we can measure the incentives, we can tell how strong they are.

Incentives Strength

The scales on the right side of the Road Map measures the strength of two important kinds of incentives. The inside right scale indicates the strength of destructive incentives, on a scale of 0% to 100%. Societies that don’t have inherent incentives that reward destruction have destructive incentives strength of ‘0%’ Societies that work in ways that send money/value to destroyers have higher numbers for ‘destructive incentive strength.’ In societies that use money to distribute value, we can measure the strength of the incentives with great precision.

The destructive incentives scale goes from 0% to 100%. In our ‘Journey Through Possible Societies’ we will consider a specific destructive act in various societies. In some societies, people can’t make any money at all doing anything destructive, including the ‘example destructive act.’ In these societies have destructive incentives strengths of 0%. Other societies work in ways that allow people to make more money destroying than the destruction costs them. These societies have destructive incentives. In the various societies we visit in the Journey, we will see that the same destructive act generates different amounts of money for destroyers. Each society has a different ‘destructive incentive strength.’ You will see that there is a certain maximum amount of money that can possibly go to destroyers. If all of this money goes to destroyers, the destructive incentives will have strength of 100%.

Societies can also work in ways that tie the right to get value or money to invention, investment, creativity, and other behaviors that can increase the bounty of the planet. Book Three explains how this works by discussing a certain very specific improvement to the world, the leveling of the land of the Pastland Farm. It shows that the costs of such an improvement will far exceed the benefits to the people who make decisions in natural law societies. As a result, people who make improvements will actually lose money on these improvements. People have incentives to improve if they make money on the improvements. Since people who make decisions do not make money on improvements in natural law societies (in fact, they lose it), natural law societies do not have constructive incentives. Note that the number on the ‘constructive incentives’ scale for natural law societies is 0%.

Other societies work in ways that do send money to people who improve the world’s ability to create value, but they send only tiny amounts of money to these people. These societies have very weak constructive incentives, indicated by very low numbers on the constructive incentives sale. Other societies send greater amounts of money to people who improve, leading to stronger constructive incentives. Since we can calculate the flows of value with great precision, we can calculate the strength of the constructive incentives with great precision. Some societies send enormous amounts of wealth to people who improve the world. These societies have very strong constructive incentives.

All the same information applies to destructive incentives. Some societies do not reward destruction at all. They have constructive incentives strength of 0%. Others do have flows of value that reward destruction, but they send only tiny amounts of money to destroyers, leading to very weak destructive incentives. Some societies send enormous sums of money to destroyers, leading to stronger destructive incentives. As you will see, there is a certain ‘maximum amount of money that can go to destroyers.’ If all of the money that can possibly go to destroyers does go to destroyers, the destructive incentives have a strength of 100%. If only part of the money goes to destroyers, the incentives strength is between 0% and 100% and if none of the money that could possibly go to destroyers goes to destroyers, the destructive incentives strength is 0%.

The Missing Section

You will note that the lower-right corner of the Road Map of Possible Societies appears to be ‘missing.’

Not all combinations of ‘ways to interact with the world’ and ‘ways to interact with other people’ can lead to functional societies.

For example, we have seen that societies built on the principle of sovereign law (the type of societies we were born into, those that accept absolute ownability of the world) are not able to function without any authoritarian bodies at all. I have gone over the reason several times already, but here is a quick recap: in these societies, groups of people that are a minority of the population (the ‘citizens’ of specific ‘sovereign nations’) claim that the majority of the people of the world (all people on earth who are not citizens of that ‘nation’) don’t have any right whatsoever to benefit from the existence of a part of the world the people who claim to own that part of the world have staked out and marked with imaginary lines. The people know that others will not simply accept that they don’t have any rights so they must be forced to accept this. The people who claim rights must use at least part of the wealth their land produces to build weapons to enforce their claims, build fortresses and other structures that defend their claims, and to pay people to man these fortresses and use the weapons to force the majority of the people of the world to respect their claims. These structures will require massive bodies with the authority to take wealth away from people (as taxes; sovereign law societies are the only societies that don’t provide any automatic income to the people of the human race that can be used for common projects). These authoritarian bodies must have the ability to organize efforts to extract resources in ways that a large percentage of ‘their own people’ may not accept. (Clear cutting forests, for example, and strip mining coal.) All societies built on this foundation absolutely require these authoritarian bodies: they can’t function without them.

The need to keep the nation ready for war, in spite of the sacrifice, suffering, poverty, and hardship this may cause for a large number of people, is one of the reasons these societies need governments to function, but not the only one. Another obvious reason for the need for governments is the stratification or hierarchical nature of sovereignty-based societies:

These societies have class hierarchies; people born into different ‘classes’ have different rights. The class that has to work to avoid death—the class that includes the great majority of the people—would not approve of these hierarchies if asked. The society must therefore be set up so that majority of the people will not have any real say in important decisions. (It may have token ceremonies that are called elections, perhaps where two people will have a kind of popularity contest to see who is the leader. But the people will never be able to control matters of any real importance in binding general elections.)

The idea of a direct democracy (system with no government or other authoritarian bodies at all) is fundamentally inconsistent with the basic principles sovereign law. As a result, it is not possible to have societies with 0% authoritarian control or very low levels of authoritarian control and have sovereign law in a real-world situation. The options at the extreme right side of the bottom line are not possible societies.

Book Three goes over all of the options on the Road Map in a scientific manner. As you might imagine, societies that are almost sovereign law societies—those with extremely high levels of ownability—will have the same basic problems as sovereign law societies, just to a lesser extent. These societies will also not be able to function without extremely powerful authoritarian bodies. If we get far enough away from sovereign law societies in the range, we will eventually get to societies that can function with extremely low levels of authoritarian control, and, at a certain point, will finally reach societies that can function without any authoritarian bodies at all.

This will leave a small area of societies at the extreme bottom right side of the map which attempt to combine the two variables in ways that nature does not allow. (You could think of this as similar to a which doesn’t slow any area that would require dividing by zero. Nature doesn’t allow dividing by zero.)

All other societies on the Road Map are possible societies. We can imagine them, we can analyze them with thought experiments to figure out how they work, we can conduct real experiments to verify the results of the thought experiments and, if we want to do this, we can build them in a real-world situation and they will function in ways that we will be able to predict using the scientific tools explained below.