16: Important Definitions

We are used to thinking about property control as all or nothing.

Either you are the owner and all rights belong to you, or you are not the owner and have no rights.

We think of it as an absolute concept; some people think it comes directly from the creator of existence and is therefore unquestionable. There are certain things that are above the power of mere humans to alter or even to fully understand: they are what they are and we must simply accept them and move on.

There was a time in our history, when anyone who proposed to use logic to understand anything at all was considered to be a damnable sinner. We are given our minds only to find better ways to worship and given free will only to test our souls for afterlife placement. But people tried to figure things out anyway. Over the course of time, people figured out more and more things and they fit together so well that people began to accept that, maybe, human minds really are capable of understanding these things.

If we let ourselves accept reality, we can see that the same is true for the concept we call ‘ownership.’ It is a mechanical concept, a structure, a tool that we can use in various ways. The discussions in the last few chapters show that it can be organized in various different ways that lead to different ‘interactions between humans and the planet earth.’

All wealth comes, in some way, from the planet earth. The way we choose to interact with the planet determines which people get this wealth and what they have to do to get it. If people can get wealth doing certain things (say destroying the world or organizing violent conflicts) they have incentives to act these ways. We all need wealth come to survive. (Food is ‘wealth.’) If we must do things that harm the world and human race itself to get wealth, there is no way to build a society without destruction and organized violence.

A group of people in the right position might do an analysis of the different ways that the tool called ‘ownership’ may work. They may determine the different settings or adjustments that can be altered to make this tool work differently. They may figure out the different incentive profiles that would be created with each set of settings and adjustments. They may then find the option that brings about the closest possible alignment between the interests of the people who wind up being the ‘owners’ of rights to make day to day decisions on the land of the planet with the interests of the human race. They may then built a society around this understanding.

Back to Pastland

Our group in Pastland passed a moratorium that prevented people from having any ownability. We created a 0% ownability society, one that had the same basic incentive structures as natural law societies.

We did not use the tool of ownership or ownability at all, for any purpose.

We can now use this tool, if we want, to give our societies incentives that help us move the human race toward a better future.

Ownership and ownability is not an all or nothing concept. It can be introduced in any ratio we want, starting with the zero ‘setting’ of the ownership tool (where this tool is set now) and turning it up by tiny increments until it starts to affect our system. Part Five does this analysis. It shows that the tool can be started at a setting of 0% ownability and then could be adjusted upward until it gets to 100% ownability. Each different ‘setting’ leads to a different incentive profile. The two extreme systems create the two societies that have existed on earth in our recent history (the last 350,000 years), natural law societies and territorial sovereignty societies. The intermediate systems create societies that have not existed in this time, but can be shown to be scientifically possible.

Ownership is a tool.

It has technical features. We can adjust these features if we understand the various technical details of this tool.

This turns out to be the thing that humans are very, very good at.

This is clearly true or we would not have nuclear weapons, ICBMs, satellites, smart phones, and the other ‘technologies’ that we currently use. Clearly, our ability understand technical details is extremely well evolved. If we are motivated enough to use these abilities, we can do technical analysis to break down a problem into tiny individual problems, come to understand each technical detail separately then put our understanding together to solve complex problems.

The main motivation behind the majority of our technology, so far, has been war. We have inherited instincts that push us to form into clans/tribes/nations, divide the world into individual parcels, and kill any members of out species that are not members of our own clan/tribe/nation that attempt to cross the lines that mark the limits of our territory. We have used our thinking abilities to build better and better weapons to help us do the things these primitive instincts (which we share with non-sapient beings including chimpanzees) push us to do.

But, in addition to being sapient, we are also ‘self aware.’ We are aware of our surroundings and our impact on them. We can see that we have already built weapons that, if used, can destroy our world and our race. If we want, we can decide that we want to use our intellectual abilities for other purposes. We can figure out ways to use the tools around us to save ourselves.

The Tool of Partial Ownability

Castle and Cooke took advantage of a system where the people who control properties aren’t really owners and aren’t really renters.

They are something in between.

When these people set up system, they needed a name to refer to it. In Hawaii, this name had to be formal because the system they built was to be backed up by a series of laws and enforceable by courts. The system in use in Hawaii is called ‘leasehold ownership.’ Technically and legally, the buyers are owners of something called a ‘leasehold.’

A leasehold is an ownable lease.

It is a long-term (or permanent) right to use a part of the world in exchange for payments made over time that are called ‘rents.’

The Basic Productivity Of The Land Important Definition

In order to intelligently discuss the concept of partial ownability of land, I need to define a few key terms that will be important in the discussions that follow.

The first is the term ‘basic productivity.’

When Annie decides to sell the leasehold to this farm, it already has a ‘basic’ or ‘preexisting capability’ to create wealth. It already has a free cash flow. You could say that a river of free wealth that is worth $2.4 million a year ‘flows’ from this land each year. This is its basic or preexisting ability to produce wealth. I need a term to refer to the amount of wealth produced to the preexisting capabilities the land already has when the current leasehold owner became the owner.

I want to use the term ‘basic productivity’ for this.

Whoever buys the leasehold will pay rents to their landlord each year. (In Hawaii, their landlord would be Castle and Cooke; in Pastland, their landlord will be the community of humankind.) Their rents will be calculated (as described below) based on the basic productive capability of the farm, not its actual production after the fact.

The landlord will want the land improved so it will create more wealth in the future. To create incentives to improve it, the landlord will let the leasehold owner keep all increases in wealth for the rest of the time she owns or for 25 years, if she owns longer than this. For this time, the rents will depend on the way the farm was before and she will pay rents based on its productivity at the time she bought it.

Definition: The basic productivity of a leasehold property is the value that the property was capable of adding to the world in its basic condition, meaning the condition it was in when the current leasehold owner became the owner.

Socratic Ownership Important Definition

In order to discuss concepts intelligently, we need names to refer to them. I want to use the term ‘socratic ownership’ to refer to partial ownership systems. If people are able to buy socratic rights to properties, they buy the right to a share of the basic productivity of the property plus the right to improve the property and have rights to the additional wealth the land produces due to the improvements.

In the examples below, the socratic owners will have very specific rights that will equate to a fourth of the rights to the basic productivity and 100% of the rights to all additional wealth the land produces. But the term ‘socratic ownership’ is a generic one that refers to any partial ownability system based on this general model:

Some rights to the world and the wealth it produces are ownable.

Other rights are not ownable and don’t belong to anyone.

Saying they are not ownable does NOT mean that the other rights belong to a ‘country’ or some other sovereign entity. If the land is part of a country that claims sovereignty over it, the country is the sovereign owner by definition and the property is controlled with sovereign ownership. Sovereign ownership is a distinct kind of ownership, one were 100% of the rights to the parts of the world involved are owned.

Socratic ownership is a system where some rights are owned (natural law societies don’t have socratic ownership because they don’t have any ownership at all) but these rights are less than 100% rights.

Socratic ownership therefore is a category of ownership that includes many different specific kinds of ownership. The examples below deal with a very specific kind of socratic ownership, one where certain rules lead to a system where ¾ of the rights to the basic productivity are unowned, where certain rights to do things that may harm the world or the people can’t be owned, but all other rights can be owned, bought, or sold. But this is just one example of socratic ownership. Later (in Part Five) we will see that there are a lot of different ways to set up socratic ownership systems, each of which can be used as a foundation for a human society.

Definition: Socratic ownership is ownership of the right to some rights to the land being owned, with the other rights being unowned. The term ‘unowned’ means that the relationship the people have with these particular rights to the land is the same as the relationship that people of natural law societies have with all land: It is not in any way ‘property’ and can’t be owned, bought, or sold by any person or group, no matter what they are called.

Important Definition: Community of humankind

We were born into societies built on the principle of territorial sovereignty. These societies work a lot like the societies of one of our evolutionary ancestors, chimpanzees. Chimps are highly and aggressively territorial animals. They mark and defend borders to their territories, organizing in ways that allow them to identify and kill any members of their species that are not members of their territorial group (any ‘foreigners’) that try to cross the borders and kill them. They organize patrols of these borders, selecting the strongest and most aggressive males to conduct these patrols, with these specific individuals given instructions and tools (to the extent of the ability of chimps to make tools) to kill any foreigners that attempt to cross their borders.

The societies that you and I inherited, and that were in place when we were born, work basically the same way. They divide the land into territories and accept that the individuals born into the territories have sovereignty over that territory: it belongs to them, they can use it as they please, and no foreigners have any rights to even walk on this land or breathe the air unless special arrangements are made to allow this. These rights (the rights to sovereignty over the land) are defended and protected the same way the highly territorial chimpanzees defend and protect the land their clan claims: using force and whatever tools and weapons they have at their disposal.

These societies divide the human race into a large number of different groups, each of which organizes itself independently of the others and claims and enforces the rights to act without regard to the needs of the other members of the human species. As of this writing, there are roughly 200 of these independent and sovereign territorial entities; this book uses the terms ‘nations’ or ‘countries’ as generic terms to refer to these entities.

In these societies, all wealth and land within each nation is claimed by that nation and belongs to that nation. Absolutely nothing is left unowned and unownable, to be used for the benefit of the human race.

In societies like this, there is nothing available to empower the human race, or give it the ability to act collectively and enforce its will and its members common needs. There is nothing to tie the entire human race together to make it a community.

The term ‘socratic ownership’ is a generic one referring to societies where some share of the wealth the world creates (some share of the basic productivity of the land) is unowned and unownable. All societies built on socratic ownability have at least some wealth that is available to empower the human race and give it authority. They have the potential to organize in ways that allow the human race to work together collectively as a community.

This book uses the term ‘community of humankind’ to refer to the human race when it is acting collectively as a community. As a practical matter, it is not possible to have a community of humankind in societies that are built on the model of chimpanzee societies, as discussed above. These societies necessarily pit each group or nation against each other group or nation.

To have a true community of humankind, the human race must be empowered in some way. Socratic ownership societies empower the human race by leaving some rights to wealth unowned and unownable, available for the members of the human race to use to meet the collective needs of the human race.

Definition: the term community of humankind refers to the human race on earth (or the race of intelligent beings on some other world) when that race has something that empowers them and allows them to work collectively to meet their common needs and goals.

Important Definition: Socratic Societies

Socratic societies are built on a foundation of socratic ownability, with the great bulk of the basic productivity of this incredibly bountiful world unowned and unownable, to be used as directed by the human race in general elections.

As a practical matter, the power of the community of humankind comes from its control over wealth. As we will see, a large part of the unowned wealth will be used for the same things we used unowned wealth for in the natural law society in Pastland: we want common services and we can use this wealth to pay people to provide them. But the world around is very bountiful and produces far more than we need for services that can be better provided in common than by simply giving people money and letting them buy what they want. We will have excess wealth. We will do the same thing with most of this excess wealth that we did in the natural law society in Pastland: we will divide it among all responsible members of the human race (all members who have accepted the basic rules that must be accepted to be a part of the community of humankind) in cash.

This is the basic idea of socratic societies. These societies are hybrid societies. They mix elements of natural law societies with elements of sovereignty based societies, creating systems that are different than both of the extremes, but have elements of both societies. We will see that they have the same general incentive profile of natural law societies in important ways: they pay people to be socially responsible (not try to ‘declare independence’ from the human race or use force to get exceptions to rules that are passed by the majority for the benefit of the majority). They pay people to be personally responsible (honest, trustworthy, kind, and respectful of the rights of others). They pay people to be environmentally responsible, to respect the world and keep it healthy, and to work with others to prevent any who don’t show this respect from doing harm to the world around us.

But they also have many of the incentives of societies that accept ownability, including territorial sovereignty societies. They have

Definition: Socratic Societies are societies where the community of humankind has decided to allow ownership of partial rights to the world. In a real-world situation, a real community of humankind may use some other form of partial ownability than socratic ownership. Societies with the community of humankind in charge that decide to have no ownership at all, or that use some other form of ownership than socratic ownership, are NOT socratic societies.

I want to define socratic societies this way because I don’t want to have to discuss the complex differences between different kinds of ownability at this point of the book. To understand these details, you have to understand a lot of complex mathematical relationships that I don’t want to go into quite yet. The easiest way to understand a partial ownability society is by example. The socratic society explained in the chapters that follow is an example of a society built on a very specific system for interacting with the planet we live on. We will look at this example in great detail. Then, we can go on to look at other systems where the community of humankind is in charge and decides to choose some other method of interacting with the land.

Why Socratics?

In the year 399BC by the calendar now in use on earth, Socrates was arrested and put on trial for heresy and corrupting youth. He had been offered a plea deal that would have gotten him off with a trivial fine (which the prosecutors had agreed to waive, because Socrates was indigent) if only Socrates would renounce his heretical ideas, claim they had all been nonsense and he hadn’t meant any of it, an apologize for the harm his joke had caused. Socrates refused their deal.

The prosecutors had no choice but to put him on trial. The trial was held in public with a jury of 501 people selected by lot. The prosecutors presented their case: Socrates was a danger to society. He claimed it was an unsound system and had to be replaced. He was actively advocating another kind of society. He had openly stated that he would not stop as long as he was alive. The only way to stop his ideas was to put him to death. The prosecutors didn’t want to do this. Their society was the epitome of perfection, with liberty and justice for all, and openly proclaimed its absolute guarantee of freedom of speech and expression. Socrates was a threat to this society and the only way to stop this threat was to put him to death. The jury was convinced; they convicted Socrates and sentenced him to death.

Why was Socrates executed?

The official charges were heresy and corrupting youth.

The crime of ‘heresy’ is essentially the same crime that George Orwell calls ‘thoughtcrime’ in his book ‘1984.’ Orwell claims that we are taught how to think as we grow up. By the time we are adults, we are supposed to understand these things. We are supposed to think a certain way. People who don’t think the way they are supposed to think are guilty of thoughtcrime.

For example, we are supposed to love our country. This presuppose the acceptance of the idea of a country: a country is a real thing, not some imaginary concept that would stop existing if the people who believed in it stopped believing in it. We are not supposed to question the principle of a country, its rightness or correctness, or whether the idea of dividing the world into countries that fight over their territorial boundaries is a beneficial thing for the human race.

Orwell claimed that we are taught techniques that help to prevent us from thinking dangerous thoughts. He calles one of these techniques ‘crimestop.’ Here he describes this technique:

The first and simplest stage in the discipline, which can be taught even to young children, is called, in Newspeak, crimestop. Crimestop means the faculty of stopping short, as though by instinct, at the threshold of any dangerous thought. It includes the power of not grasping analogies, of failing to perceive logical errors, of misunderstanding the simplest arguments if they are inimical to Ingsoc, and of being bored or repelled by any train of thought which is capable of leading in a heretical direction. Crimestop, in short, means protective stupidity.

We are supposedto understand and use this technique. This protects us from dangerous ideas like the ones Socrates clearly thought and was even brave enough to talk about. We are supposed to realize, before we even think these thoughts, that they are wrong. Socrates hadn’t learned this lesson. He let his mind go in places which he knew in advance were prohibited. He committed the crime of heresy.

He was particularly dangerous because he spread his ideas to young people, including people who hadn’t fully accepted the basic principle of crimestop and couldn’t instinctively filter ideas they got from the outside world to prevent dangerous ideas from entering their minds. They listened to Socrates and he made sense. Once they had this sate of mind, their minds had been ‘corrupted.’ They didn’t work the way our minds are supposed to work. This had to be stopped.

The authorities didn’t want to have to put Socrates on trial, because the knew a trial would expose their hypocrisy: they claimed freedom of thought, words and expression. In fact, this was the very thing their troops had been fighting and killing enemies to protect. It was why their country existed, or so they said: to protect these wonderful ideals. If they put Socrates on trial for the things he thought, they would reveal that their country really didn’t have the wonderful characteristics that they claimed they had to fight and kill others to protect. Socrates had told them that war was simply a mechanical side effect of the operation of the strucures of societies that divide the world into independent and sovereign territorial units (πολιτείες, to use Socrates word for these societies). War is inevitable. The claims that they were fighting to protect freedom and democracy were nonsense bits of propaganda. By putting Socrates on trial, they would be proving his points for him. That is why they offered him the wonderful deal they offered him: he would be let go and live the rest of his life without problems from the law if only he would renounce his ideas, claim they were just jokes, and apologize for the harm these jokes caused.

The book ‘The Apology,’ written by Plato, includes transcripts of the testimony Socrates gave at his trial, defending his position. Socrates is explaining why he would not issue the apology that would have saved his life: he would not apologize for trying to make the world better. If his only alternative was to accept death, he would accept death. Many, many people had accepted death for causes of far lesser importance. (Millions had died ‘for their countries’ in wars, even though an objective analysis would show that the wars had not accomplished anything positive and were incapable of doing so. They simply moved the imaginary lines called ‘borders’ a little bit in one or another direction: this does not make the world better.)

Socratic Ownership

After the sentence had been carried out and Socrates was dead, his papers were collected and destroyed. We have not a single word from his own hand. However, one of the young people who had been corrupted by Socrates, Plato, was from one of the richest and most powerful families in the entire country. Plato knew better than to openly discuss Socrates ideas: he didn’t want to meet the same fate. But he had inherited a large and heavily fortified retreat. (One of his ancestors, nicknamed ‘the Tyrant of Athens,’ had built this retreat to have a place where he could go and be safe from his many enemies.) It has only one entrance, 30 ft high walls with guard towers, and was totally private. It had been named after a Greek war god, Akademos, and was called ‘the Academy.’

Plato organized a secret society to meet in the Academy to discuss the basic ideas Socrates had discussed. Plato wrote a series of books called ‘Socratic dialogues’ that are basically the text of conversations that Socrates had with various people discussing his ideas. These books where published, at Plato’s expense, with the originals kept in a library that Plato had built in the Academy called the ‘Lyceum.’ The idea was spread (out of the view of the governments of course; merely thinking the dangerous thoughts could be punished by death) that people could come to the Academy and meet with others who didn’t accept the standard views of society and wanted something better, without having to worry about being arrested for being willing to think the heretical thoughts.

Three of the socratic dialogues present a coherent trilogy that lays out Socrates basic ideas about society. The first book in the series is called ‘πολιτείες .’ This book would be pronounced ‘politikas.’ This book deals with the realities of societies that divide the world into political units that are independent and sovereign. (The term πολιτείες ’ translates literally into ‘independent and sovereign states.’)

Socrates claims that such societies are fundamentally unsound and can never meet the needs of the human race. Again, I want to use the exact word he used: δικαιοσύνη. (This word would be pronoucned ‘dikosey.’) Socrates used this word to represent characteristics that a societies must have to meet the needs of the production in it. A societies with ‘δικαιοσύνη’ is one that can operate in a smooth, sound, logical way and is at least capable of social, personal, and environmental responsibility and harmony. Societies that divide the world into ‘states’ (‘πολιτείες’) could never have ‘δικαιοσύνη’

In the book πολιτείες (politikas) Socrates explains the reason these societies can never have δικαιοσύνη: these divisions are built on conflict and can’t exist without it. The conflict is violent and nations that aren’t properly organized for to carry out conflict with the best weapons and tactics available will be defeated by those that are. The primary needs of these societies involve capability in war. War is organized mass murder and destruction. This is a foundational element of the nation-based societies (πολιτείες). It is not possible to start with this as a foundation and build a sound society (one with δικαιοσύνη).

If we want sound societies, we need to accept that societies that divide the world this way are only one of the many possible types of societies people can form. We must accept we are capable of more.

The second book in the series is called the Critias. This book describes natural law societies. It starts by talking about a continent on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. This continent is inhabited but the people there live differently than the societies of Socrates’ part of the world. Their societies were not built on the absolute rights of ‘nations.’

Many attempts were made to destroy all of the ideas of Socrates and the people influenced by him. Entire libraries were burned to the ground to destroy the dangerous works. (The Lyceum was not only burned to the ground, it was dismantled, along with all of the rest of the Academy, brick by brick, with the bricks removed to other areas so they couldn’t be identified with the Academy. The foundations were rediscovered by an amateur archeologist in the 1960s and architects and engineers have been able to build models based on ancient drawings and reverse-engineering of the foundations to determine the height of the walls and size of the buildings). Unfortunately, large parts of the Critias were lost entirely and we only understand the basic ideas of the book itself from the fragments that remain.

Socrates didn’t claim that the other societies the book explained were perfect. In fact, he clearly goes out of his way to claim that these societies have deep flaws and can’t meet the needs of the human race (can’t have δικαιοσύνη). But their flaws are entirely different than the flaws of the πολιτείες (politika) societies. This tells us something very important: other societies are possible. The πολιτείες societies are not the only possible societies.

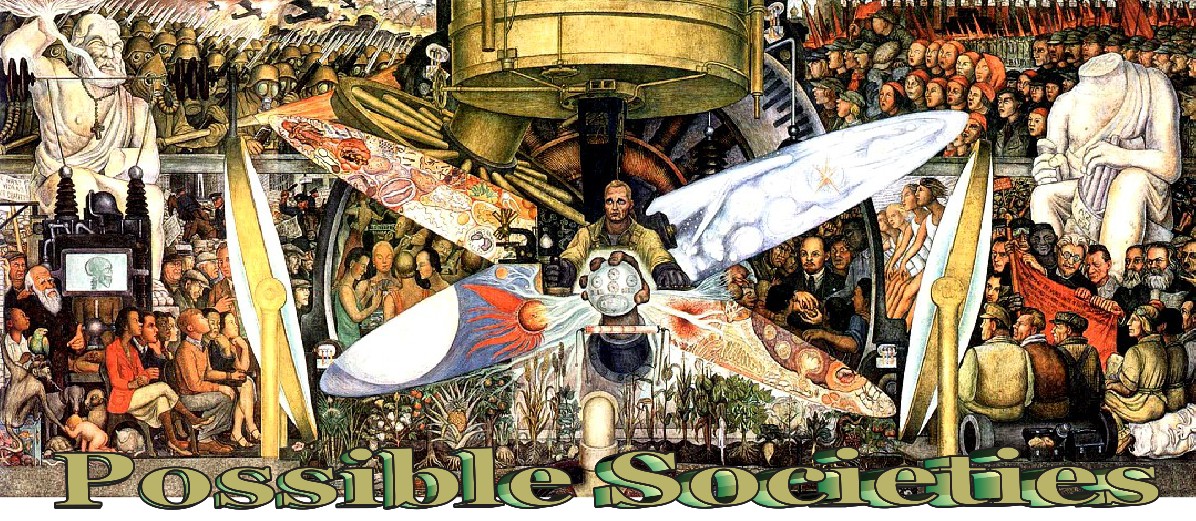

The third book in the series, Timaeus, presents the same ideas as Part Six of Possible Societies (preventing extinction)’ It deals with the idea of creating a society with δικαιοσύνη, when you must start from societies that operate like the animalistic territorial societies that divide the world with imaginary lines and use organized mass murder to defend these lines. Again, we don’t have the complete book and there are a lot of missing links and incomplete arguments, but we have enough to get the general idea. Sound societies (societies with δικαιοσύνη) are possible. They can exist. We can create them, if we are able to open our minds to ways of thinking that the societies of our birth actively discourage and even try to prohibit. We are on the same path we were on 2,400 years ago, a path that clearly leads to extinction. We are obviously much closer to this destination now than we were 2,400 years ago, but the end was just as obvious then as it is now.

Socrates heretical thought was this: we don’t have to go down this path. Other paths are possible.